Français / Español / 简体中文 / русский / العربية / 日本語

© 2026 World Federation of Hemophilia

Hemophilia is a rare bleeding disorder. For many years, people believed that only men and boys (or males) could have symptoms of hemophilia, such as bleeding in general and bleeding into joints, and that women who “carry” the hemophilia gene do not experience bleeding symptoms themselves.

We now know that many women and girls do experience symptoms of hemophilia. As our knowledge about the disorder has increased, so has our understanding of why and how women can be affected. Some women live with their symptoms for years without being diagnosed or even suspecting they have a bleeding disorder. Through education and awareness-raising, the World Federation of Hemophilia is working to close this gap in care.

What is hemophilia?

Hemophilia is a genetic bleeding disorder. People with hemophilia bleed for longer than normal because their blood does not contain enough clotting factor, or the clotting factor doesn’t work properly. Clotting factors are proteins in the blood that help control bleeding.

There are two types of hemophilia: hemophilia A and hemophilia B. Hemophilia A is more common; people with hemophilia A do not have enough clotting factor VIII (factor 8). People with hemophilia B do not have enough clotting factor IX (factor 9).

Hemophilia is usually inherited, meaning that it is passed from parent to child through the parent’s genes. Genes carry messages about the way the body’s cells will develop. They determine a person’s hair and eye colour, for example. In people with hemophilia, the genes responsible for the production of clotting factors are altered or changed. As a result, their body will either not produce sufficient or any clotting factor, or the clotting factor it produces does not work properly.

Inside each cell of the body, hereditary information and instructions for building proteins for body parts (eyes, hair, skin, blood etc.) are carried in a coiled structure called DNA (deoxy ribonucleic acid). Genes are small segments of DNA and are packaged on structures called chromosomes. There are 23 pairs of chromosomes that includes a pair of “sex chromosomes” termed X and Y chromosomes. The genes involved in hemophilia are located on the “X” chromosome.

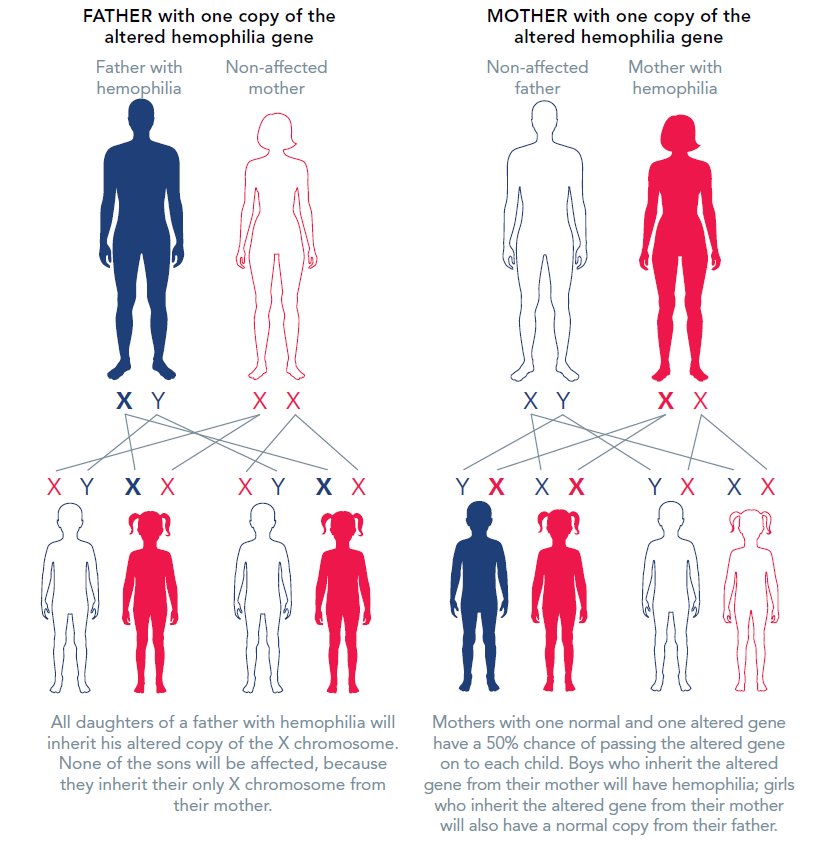

The X chromosome is called the “sex chromosome” because it plays a role in determining whether a person is male or female. Men have one X chromosome, which they inherit from their mother, and one Y chromosome, which they inherit from their father. Women have two X chromosomes: one from each parent.

If the X chromosome a man inherits from his mother has the altered, mutated, or changed gene that prevents the clotting protein from working properly or to be missing altogether, he will have hemophilia. If a woman inherits a copy of the altered gene from either of her parents, she will have one normal and one altered (or mutated) copy of the gene.

INHERITANCE OF HEMOPHILIA

Lyonization

In each cell in a woman’s body, one of the two X chromosomes is turned off, or “suppressed”. This process is called “lyonization”, after Mary Lyon, who first described it. Lyonization is a random process that is not fully understood.

If the chromosome that is turned off has the altered gene, that cell will produce normal levels of clotting factor. If the chromosome with the normal gene is turned off, the cell will not produce clotting factor, or the clotting factor it makes will not work properly.

On average, women who have inherited one altered copy will have about 50% of the normal amount of clotting factor, because about half of their cells will have the “good or normal” gene turned off. Some women will have far lower levels of clotting factor because more of the X chromosomes with the normal gene are switched off.

There are three levels of severity of hemophilia: mild, moderate, and severe. The severity of hemophilia depends on the amount of clotting factor in the person’s blood.

| Mild hemophilia |

5% – 40% of the normal amount of clotting factor |

| Moderate hemophilia |

1% – 5% of the normal amount of clotting factor |

| Severe hemophilia |

less than 1% of the normal amount of clotting factor |

In 2021, as per the International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, a new nomenclature was established to define hemophilia in women and girls as the term “hemophilia carrier” can hamper diagnosis, clinical care, and research. The new nomenclature is based on bleeding symptoms and factor levels resulting in five clinically relevant categories:

Approximately one third of women and girls with the affected hemophilia gene have clotting factor levels below 40% of normal, which may lead to abnormal bleeding. Women with levels over 40% of normal may also have bleeding symptoms. In most cases, these women experience symptoms similar to those seen in men with mild hemophilia, as well as some that are specific to women, such as prolonged or heavy menstrual bleeding.

Symptomatic hemophilia carriers and women and girls with hemophilia:

Bleeding after surgery or trauma

Studies have shown that the most common symptom women experience is prolonged bleeding after surgery, such as a tooth extraction, tonsillectomy, placement of intrauterine devices, hysterectomies, cesarian delivery, appendectomy, and breast and other biopsies. They are also at risk of serious bleeding after an accident or injury.

Heavy menstrual bleeding

Women with low factor levels have a greater risk of heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding. Girls may have especially heavy bleeding when they begin to menstruate. Excessive blood loss can lead to anemia due to low levels of iron in the blood, resulting in weakness and fatigue.

Menstrual pain, cramps and mid-cycle pain

Women with hemophilia and symptomatic hemophilia carriers are more likely to experience pain during their menstrual bleeding (dysmenorrhea). They may also experience a small amount of internal bleeding during ovulation, which can cause abdominal and pelvic pain (known as Mittelschmerz, a German word meaning “middle pain”). This bleeding can be severe or even life-threatening, especially in women with very low clotting factor levels, and may require urgent medical attention.

Perimenopausal bleeding

Menopause is the time in a woman’s life when menstrual periods permanently stop. Perimenopause is the 3- to 10-year period before menopause when hormones are “in transition.” Heavy and irregular menstrual bleeding is common for all women as they approach menopause. Gynecological conditions (such as fibroids, polyps, etc.) are also more common at this stage of life. Women with hemophilia are at risk of more severe bleeding symptoms and may require treatment.

Other gynecological problems

During the process of ovulation, all women can develop simple (also called functional) ovarian cysts. These cysts are usually small, do not cause any problems, and go away on their own. Women with hemophilia have a greater risk of bleeding into these simple cysts, which then become “hemorrhagic” ovarian cysts. Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts can cause considerable pain and may require urgent medical intervention.

Some women with hemophilia or symptomatic hemophilia carriers also suffer from endometriosis, a painful condition in which endometrial tissue, the tissue that lines the uterus, forms in the abdomen or other parts of the body. Although we do not yet understand the cause of endometriosis, women who experience heavy menstrual bleeding are more at risk of developing the condition.

Joint disease

Women and girls with hemophilia and symptomatic hemophilia carriers are vulnerable to joint damage and disease, and may show changes in joints on X-rays and MRI or imaging studies, as well as experience reduced joint range of motion. This may manifest as joint pain and is sometimes mistaken for arthritis. Some women also experience joint bleeding that may not be physically evident (subclinical joint bleeding).

There are two types of women with hemophilia: those who necessarily have the hemophilia gene, which they inherit from their father, and those who can be identified by getting a detailed family history (known as a pedigree).

Those who necessarily have the hemophilia gene are:

Those who are identified through a detailed family history are:

Many women, even those with many close relatives with hemophilia, are unaware of their status. Compared to boys, age at diagnosis is often delayed in girls.

Bleeding Assessment Tool, Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart, and laboratory tests

Bleeding Assessment Tools (BAT) are questionnaires about bleeding symptoms that result in a quantitative bleeding score. They are effective measures of bleeding severity and use a series of questions regarding presence or absence of bleeding symptoms and the level of medical attention and intervention required for each.

Women and girls with hemophilia and symptomatic hemophilia carriers have a higher bleeding score than women without a bleeding disorder. The most commonly used BAT is a validated tool called the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis – Scientific and Standardization Committee (ISTH-SSC) BAT.

The Pictorial Blood Assessment Chart (PBAC) is a tool to assess daily menstrual blood loss that captures the number of pads and tampons and the intensity of blood stains on the pads and tampons. The PBAC score determines if a woman or girl has normal or heavy menstrual blood loss. A score of >100 indicates heavy menstrual bleeding.

Two kinds of laboratory tests can be performed for women who think they might have hemophilia: factor assays and genetic tests.

Factor assays measure the amount or level of clotting factor in a person’s blood. While this information is useful, some women have normal clotting factor levels. Therefore, this test has the potential to provide falsely reassuring or incorrect information to women who may indeed have hemophilia; it cannot be used to rule out hemophilia.

Factor levels can vary significantly among family members. For example, a woman with very low factor levels can have a daughter whose levels are near normal. Factor assays should therefore be done for each woman within a family.

Stress, inflammation, infections, certain medications, birth control pills, and pregnancy can all cause factor VIII levels to rise and therefore affect test results. Factor VIII levels also tend to go up as people get older.

Genetic tests, such as mutation analysis, look directly for the altered gene that is responsible for hemophilia. This is the only way to be absolutely sure that a woman has hemophilia (or is a symptomatic or asymptomatic hemophilia carrier). Information obtained from genetic tests may be useful for other family members. However, genetic tests can be costly and may not be available in all centres.

Diagnostic testing for women and girls is a complex issue. While it is important for safety reasons to know a suspected woman’s factor levels, genetic testing raises several ethical and cultural concerns.

Since women with hemophilia and symptomatic hemophilia carriers can be at risk of bleeding following trauma, tooth extractions, or other surgeries, it is a good idea to have factor levels measured in all suspected or known carriers, as early as possible, so that extra precautions can be taken if factor levels are low. In cases of suspected hemophilia A, factor VIII assays can be performed at birth from cord blood sample. On the other hand, factor IX levels in hemophilia B are naturally low at birth and reach normal levels by six months of age. However, factor levels alone cannot confirm a woman’s diagnosis.

The decision to undergo genetic testing is shaped by the family’s perceptions and cultural concerns, but also whether testing is accessible and/or permissible by regulatory bodies (i.e., government, insurance providers). In some countries, only the woman herself can consent to genetic tests — it is not a decision her parents can make for her.

Where genetic testing is possible before the child reaches the age of consent, families often struggle to determine when to test for hemophilia status. Many wonder whether they should have their daughters tested during childhood, specifically before they begin menstruating, or wait until they become adults and can make the decision themselves. Where possible, testing should be performed before a woman becomes pregnant or has surgery.

Some families delay testing as a form of denial, or to protect the child and themselves from what they perceive as bad news. Cultural issues, such as arranged marriages or the possibility of the daughter having an affected child of her own, may discourage some families from having a daughter tested. Others test routinely as a matter of course, letting the child grow up with the knowledge of their diagnosis. Knowing their status early can also help girls come to terms gradually with the complex reality of having hemophilia or being a symptomatic or asymptomatic hemophilia carrier.

Before making a decision, parents should consider their daughter’s readiness to manage with the information about her potential hemophilia status. Factors like her age, emotional maturity, and level of understanding and interest in the information need to be considered. A girl’s anxiety may be higher if she has seen a family member suffer because of hemophilia, or if she does not know, with certainty, whether she is a hemophilia carrier or not. Feelings of anger or jealousy between siblings can arise if one of the siblings requires special attention for their bleeding disorder, while another is ignored. Anxiety can also surface with regards to having a child with a bleeding disorder. These are all normal and common reactions.

In all cases, families should consult with the specialists at a hemophilia treatment centre, including a genetic counsellor or psychosocial professional, who can help them through the decision process and offer follow-up counselling, if necessary.

Women with hemophilia and hemophilia carriers should receive preconceptual counselling (that includes genetic counselling) about the risks of having a child with hemophilia, well in advance of a planned pregnancy, and should be seen by an obstetrician as soon as they suspect they are pregnant. The obstetrician should work closely with the staff of a hemophilia treatment centre to provide the best care during pregnancy and childbirth, and to minimize potential complications for both the mother and the newborn.

Before getting pregnant, women need clear and accurate information about:

Some people simply accept the possibility of having a child with hemophilia. In countries where quality care with safe clotting factor concentrates is available, hemophilia is often seen as a manageable disease. Where adequate care is not available, this is a more difficult decision. Some families choose to adopt or foster a child, or to use other conception options to eliminate the risk of having a child with hemophilia. However, these options are not always available or can be unacceptable for religious, ethical, financial, or cultural reasons.

| Procedure | How it’s done | Things to consider |

|---|---|---|

|

In-vitro fertilization (IVF) with pre-implantation diagnosis (PGD) |

The woman’s eggs are retrieved and fertilized in the laboratory with the sperm from the woman’s partner. This is called IVF. When the embryos are at a very early stage of development, a test is done to determine whether they carry the altered hemophilia gene. Only those that do not contain the altered gene are implanted into the mother’s womb. |

This procedure is expensive and not available in many parts of the world. The success rate for a pregnancy with IVF is approximately 30% per cycle. CVS or amniocentesis is still recommended to confirm that the fetus does not carry the altered gene. |

| IVF with egg donation | Using donor eggs from a fertile woman who is not a carrier of hemophilia ensures that the child would not be at risk of inheriting the hemophilia gene from the mother. | Again, IVF is expensive, with a success rate for pregnancy of approximately 30% per cycle. The success rate is best when the donor is young. |

| Sperm sorting |

Only sperm carrying an X chromosome is used. This ensures the birth of a female child. |

The female child may still inherit the altered gene and have hemophilia. She could experience bleeding symptoms and may pass the altered gene on to her children. This method is only available in specialized centres as a research tool, and it is still under evaluation. |

Couples who have conceived naturally may wish to know whether their child is affected by hemophilia before he or she is born.

A definitive prenatal diagnosis can only be offered with invasive procedures such as amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling. Some centres only offer these procedures if the couple plans to terminate the pregnancy if the fetus is found to have hemophilia. The decision to terminate a pregnancy is an extremely difficult one, which may not be acceptable for personal, religious, ethical, or cultural reasons.

Amniocentesis: A small amount of amniotic fluid is removed, using a fine needle inserted into the uterus through the abdomen. Amniocentesis is carried out under ultrasound guidance, between the 15th and 20th week of pregnancy. The amniotic fluid contains cells from the fetus that can be analyzed to detect hemophilia.

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS): Under local anesthesia and ultrasound guidance, a fine needle is inserted through the abdomen or a thin catheter is inserted through the mother’s vagina to take a sample of chorionic villi cells from the placenta. These cells contain the same genetic information as the fetus itself and can be used to determine whether the fetus is affected by hemophilia. This procedure is performed early—between the 11th and 14th weeks of pregnancy. CVS is the most widely used method for the prenatal diagnosis of hemophilia and other inherited bleeding disorders.

The risk of miscarriage associated with CVS or amniocentesis is up to 1%.

Pregnant women may also be offered non-invasive testing to determine the sex of the fetus they are carrying. This is done through testing the mother’s plasma for fetal cells that contain fetal DNA.

Fetal sex determination, which is finding out whether the baby is a boy or girl, is a relatively simple procedure. Knowing the sex of the fetus does not tell you if it is affected by hemophilia, but it does provide useful information.

If the fetus is male, and therefore has a greater likelihood of having hemophilia, CVS or amniocentesis can be offered to parents who wish to know whether he is affected with hemophilia. If the parents choose not to have CVS or amniocentesis, or if these tests are not available, doctors should plan labour and delivery to minimize the chance of bleeding in a male fetus (see “Labour and delivery: considerations for mother and child”).

If the fetus is female, prenatal diagnosis is not necessary because, even if the female child has hemophilia, there is very little risk of bleeding for the baby during labour and delivery.

The sex of the fetus can be determined in two ways:

Most women with hemophilia or hemophilia carriers have normal pregnancies without any bleeding complications. Levels of factor VIII increase significantly in pregnancy, which reduces the risk of bleeding for hemophilia A. Levels of factor IX, however, do not usually change significantly.

Factor levels should be tested in the third trimester of pregnancy, when they are at their highest. If levels are low, precautions should be taken during labour to reduce the risk of excessive bleeding. Women with hemophilia are at risk for postpartum hemorrhage, not only those with low levels but also those with normal levels of FVIII/IX. Postpartum hemorrhage occurs in approximately 20% to 50% of deliveries.

The obstetrician should work closely with the members of the hemophilia treatment centre to make sure the pregnancy is properly managed.

Planning for birth depends on the needs of the mother and her potentially affected child.

It is difficult to measure clotting factor levels during labour, so this should be done in the last trimester of pregnancy. If factor levels are low, treatment may be given during labour to reduce the risk of excessive bleeding during and after childbirth. Clotting factor levels may also determine whether a woman can receive local anesthesia (an epidural).

There is an increased risk of head bleeding in affected male babies, especially if the labour and delivery have been prolonged or complicated. Women with hemophilia may give birth vaginally, but prolonged labour should be avoided, and delivery should occur in the least traumatic way possible. Invasive monitoring techniques such as fetal scalp electrodes and fetal blood sampling should be avoided whenever possible. Delivery by vacuum extraction and forceps should also be avoided.

As soon as the baby is delivered, a sample of blood from the umbilical cord should be collected to measure clotting factor levels. Injections into the baby’s muscle tissue and other surgical procedures, such as circumcision, should be avoided until the results of these blood tests are known.

Postpartum care

After delivery, a woman’s circulating clotting factor goes back down to her pre-pregnancy level and the chance of bleeding is at its highest.

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is a major cause of maternal death and disability, especially in some parts of the world. Therefore, women with hemophilia and symptomatic hemophilia carriers should be cared for in an obstetric unit with close collaboration with the hemophilia team. Factor concentrate should be administered to prevent bleeding in those whose levels are low or those undergoing caesarean delivery. Desmopressin (also known as DDAVP) can be given after the umbilical cord is clamped and attention paid to fluid restriction. Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, has proven efficacy for preventing PPH. Intravenous tranexamic acid given within 3 hours of vaginal or caesarean birth is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in all cases of PPH regardless of the cause.

Certain precautions can be taken to reduce the risk of PPH: medications that keep the womb contracted can be given, and the placenta should be delivered by controlled traction of the umbilical cord. This is called “active management” for placenta delivery and has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of PPH.

Women with hemophilia and symptomatic carriers are at risk of PPH for up to six weeks after childbirth and should be advised to see their doctor immediately if bleeding is excessive during this period. Treatment may be recommended as a preventative measure, especially in women with low clotting factor levels.

Women with hemophilia and symptomatic carriers usually don’t experience symptoms daily. They may, however, experience prolonged bleeding after an accident or medical intervention. When this happens, they must be treated in the same way as men with hemophilia.

Desmopressin (DDAVP)

Desmopressin is a synthetic hormone that may help control bleeding in an emergency or during surgery. It can be injected intravenously, administered under the skin (subcutaneously), or given as a nasal spray.

Desmopressin does not work for every woman. All women with hemophilia A with clotting factor levels of less than 50% should have their response to the medication tested before they need to use it. Desmopressin is not effective for hemophilia B, as it does not raise levels of factor IX.

Desmopressin should not be used in some instances, for example, in cases of head trauma and in women who are at risk of heart problems. Doctors should be familiar with the medication and how it should be used before prescribing it.

Clotting factor concentrates

In women for whom desmopressin doesn’t work or is not recommended, infusions of clotting factor concentrates may be necessary when the risk of severe bleeding is high, such as before or during surgery.

Antifibrinolytic agents

The antifibrinolytic drugs tranexamic acid and aminocaproic acid, given orally or intravenously, are used to prevent the breakdown of blood clots in certain parts of the body such as the mouth and uterus. They can be used to control heavy menstrual bleeding and during minor surgeries and dental procedures.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy can be used to help control excessive menstrual bleeding. This includes combined hormonal contraceptives (which can be given orally, as skin patches, or vaginally) and the levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system (IUD or IUS).

Surgical options for menorrhagia

Some women will continue to experience heavy menstrual bleeding, even with these medications. Though there are always some risks involved in surgery, it may be considered in rare circumstances.

Uterine (or endometrial) ablation

In this procedure, the lining of the uterus (the endometrium), what is shed during menstruation, is permanently destroyed. The operation is done through the vagina, so no surgical cutting is needed. Though quite effective at reducing menstrual flow, this procedure reduces a woman’s ability to become pregnant and interferes with normal pregnancy. It is therefore not recommended for women who want to have children.

Hysterectomy

A hysterectomy is the complete removal of the uterus to permanently stop menstrual bleeding. This is a serious procedure that is not an option for people who want to become pregnant. Sometimes, the ovaries and the fallopian tubes are also removed. A woman who has had a hysterectomy can no longer have children.

Being a “carrier of hemophilia” can have a significant impact on a woman’s health and her academic, professional, and social life. Often the diagnosis is delayed due to limited awareness on part of the individual or the health care provider.

Excessive or prolonged menstrual bleeding can be especially difficult for young girls, who may isolate themselves from family and friends, miss days from school, or avoid social events due to pain, discomfort, or the fear of staining clothing. A girl’s self-image and confidence can be negatively affected if she experiences shame or embarrassment because of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Many women and girls are not aware that their symptoms are abnormal and do not seek medical advice. Even when they do, caregivers are not always well informed about bleeding disorders and the right diagnosis may be overlooked. Furthermore, medical care for women is lacking in many countries around the world. There may be cultural taboos and obstacles preventing women from seeking help, particularly for menstrual problems. Distance, disease severity, age, stigma, and language barriers also impact early diagnosis.

Heavy and prolonged menstrual bleeding and pain can affect a woman’s sexuality and may cause problems in her marriage. Women may also need to take time off work each month because of heavy bleeding, which can impact their career choices or professional success.

Many women with hemophilia, and symptomatic and asymptomatic hemophilia carriers, like others at risk of passing on a genetic disease, also experience guilt. They may feel as though they should not have children because of the possibility of passing on a bleeding disorder or having a daughter who must face this possibility in turn.

The prospect of marriage may be affected because men, or their families, may not accept the risk of having an affected child. If they do have children with hemophilia, the needs of that child can put pressure on all family members, including siblings.

Many hemophilia treatment centres can provide women and girls with skilled and sensitive counselling. The professionals there can provide information and support to work through these complex feelings and to empower women to take charge of their condition and advocate for proper treatment. Building a support network of other women who are facing the same issues, through the hemophilia treatment centre or local patient organization, can be a great source of comfort.

Source: WFH Guidelines for the Management of Hemophilia, 3rd edition (2020). For more detailed information about hemophilia, please refer to the guidelines at https://elearning.wfh.org/resource/treatment-guidelines/