Français / Español / 简体中文 / русский / العربية / 日本語

© 2026 World Federation of Hemophilia

Hemophilia is a bleeding problem. People with hemophilia (PWH) do not bleed any faster than normal, but they can bleed for a longer time, because their blood does not have enough clotting factor. Clotting factor is a protein in blood that controls bleeding.

Hemophilia is considered a rare disease. The most common type of hemophilia is called hemophilia A. People with hemophilia A do not have enough clotting factor VIII (factor eight). About 21 of every 100,000 males have hemophilia A. A less common type is called hemophilia B. People with hemophilia B do not have enough clotting factor IX (factor nine). About 4 in 100,000 males have hemophilia B. The result is the same for people with hemophilia A and B; that is, they bleed for a longer time than normal.

For many years, people believed that only men and boys (or males) could have symptoms of hemophilia, such as bleeding in general and specifically bleeding into joints, and that women who “carry” the hemophilia gene do not experience bleeding symptoms themselves. We now know that many women and girls do experience symptoms of hemophilia.

People are born with hemophilia. They cannot catch it from someone, like a cold.

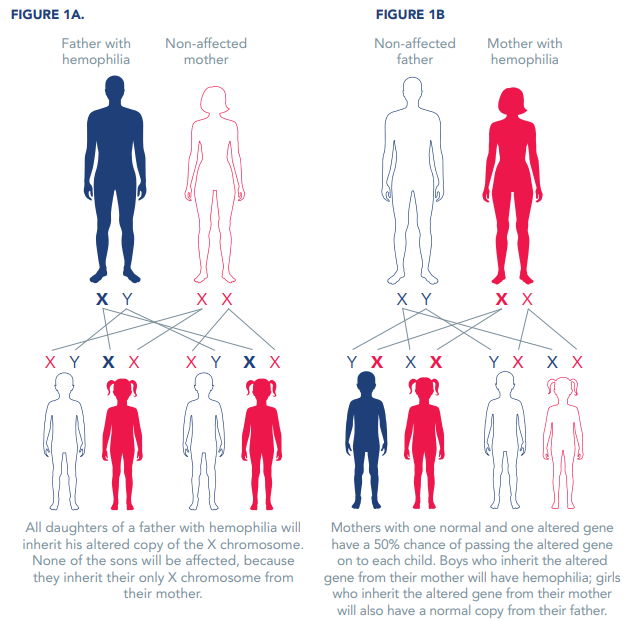

Hemophilia is usually inherited, meaning that it is passed on through a parent’s genes. Genes carry messages about the way the body’s cells will develop as a baby grows into an adult. For example, genes determine a person’s hair and eye colour.

The hemophilia gene is passed down from parent to child. The genes for hemophilia A and B are on the X chromosome. For this reason, hemophilia is called an X-linked disorder.

All daughters of a father with hemophilia will inherit his altered copy of the X chromosome. None of the sons will be affected, because they inherit their only X chromosome from their mother (Figure 1A).

Mothers with one normal and one altered gene have a 50% chance of passing the altered gene on to each child (Figure 1B). Boys who inherit the altered gene from their mother will have hemophilia; girls who inherit the altered gene from their mother will also have a normal copy from their father. On average, women and girls with the hemophilia gene will have about 50% of the normal amount of clotting factor, but some have far lower levels of clotting factor and can show signs of hemophilia. In fact, estimates suggest that for each male with hemophilia, an average of three female relatives will be affected.

Sometimes hemophilia can occur when there is no known family history, such as from spontaneous mutations in the person’s own genes. In these cases, it is caused by a change in the person’s own genes.

In rare cases, a person can develop hemophilia later in life – this is called acquired hemophilia, an auto-immune disorder rather than an inherited bleeding disorder. Most of these cases involve middle-aged or elderly people, or young women who have recently given birth or are in the later stages of pregnancy. This condition is not inherited and often resolves with appropriate treatment.

The severity describes how serious a disease is. There are three levels of severity of hemophilia, measured in percentage of normal factor activity in the blood, or in number of international units (IU) per millilitre (mL) of whole blood. The normal range of clotting factor VIII or IX in the blood is 40% to 150%. People with factor activity levels of less than 40% are considered to have hemophilia, as per Table 1. Some people’s bleeding pattern does not match their baseline level. In these cases, the phenotypic severity (bleeding symptoms) is more important than the baseline level of factor in deciding upon treatment options.

Table 1

| Severity | Clotting factor level | Bleeding episodes |

|---|---|---|

| Mild hemophilia |

5% to < 40% of normal (or 0.05-0.40 IU/mL) |

|

| Moderate hemophilia |

1% to 5% of normal (or 0.01-0.05 IU/mL) |

|

| Severe hemophilia |

< 1% of normal (or < 0.01 IU/mL) |

|

*Adapted from Table 2-1 of the WFH Guidelines for the Management of Hemophilia, 3rd edition

The signs of hemophilia A and B are the same, and include:

Bleeding into a joint or muscle causes:

Approximately one third of women with hemophilia have clotting factor levels of less than 60% of normal and may experience abnormal bleeding. In most cases, they experience symptoms similar to those seen in men with mild hemophilia, as well as some that are specific to women, such as prolonged or heavy menstrual bleeding, and more likely to have postpartum bleeding following childbirth.

Table 2 – Sites of bleeding in hemophilia

| Serious |

|

| Life-threatening |

|

*Adapted from Table 2-2 of the WFH Guidelines for the Management of Hemophilia, 3rd edition

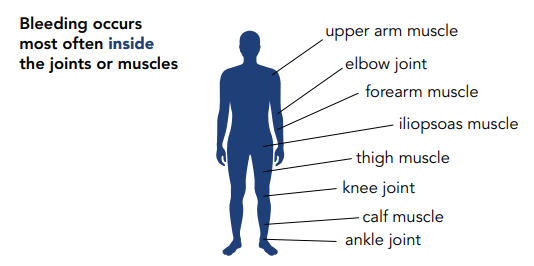

PWH can bleed inside or outside the body. Most bleeding in hemophilia occurs internally, into the muscles or joints. The most common bleeding sites are the ankles, knees, and elbows. The most common muscle bleeds occur in the muscles of the upper arm and forearm, the iliopsoas muscle group (hip flexors), the thigh, and the calf.

If bleeding occurs many times into the same joint, the joint can become damaged and painful. Repeated bleeding can cause other health problems like arthritis. This can cause pain and can make it difficult to walk or do simple activities. However, the joints of the hands are not usually affected in hemophilia (unlike some kinds of arthritis).

In newborns and young children with severe hemophilia, the most common types of bleeding are:

Since most bleeds will happen outside of hemophilia treatment centres (HTCs), it is important for patients and caregivers to be taught about:

Hemophilia is diagnosed by taking a blood sample and measuring the level of factor activity in the blood. Hemophilia A is diagnosed by testing the level of factor VIII activity. Hemophilia B is diagnosed by measuring the level of factor IX activity.

Prenatal diagnosis testing can be performed in early pregnancy by taking a small sample from the fetal part of the placenta (chorionic villus sampling) or by taking blood from the fetus (late-gestation amniocentesis) at a later stage. Testing can also be done from the umbilical cord.

These tests can be facilitated by an HTC.

Treatment for hemophilia today is very effective. With an adequate quantity of treatment products and proper care, PWH can live perfectly healthy lives. Without treatment, most children with severe hemophilia will die young. An estimated 800,000 people worldwide are living with hemophilia and many do not receive adequate treatment. The World Federation of Hemophilia is striving to close this gap.

Standard and extended half-life clotting factor concentrates (CFCs) are an important treatment option for hemophilia and are given as intravenous infusions. They can be made from human blood (called plasma-derived products) or manufactured using genetically engineered cells that carry a human factor gene (called recombinant products). Factor concentrates are made in sophisticated manufacturing facilities. All commercially prepared factor concentrates today are treated to remove or inactivate blood-borne viruses. Extended half-life (EHL) CFCs last longer in the body, and were developed to ease the burden for PWH on prophylaxis and maintain higher clotting factor levels to improve bleed prevention.

Bypassing agents, such as activated prothrombin complex concentrates (APCC) and recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa), are used to treat acute bleeding in people with hemophilia A or B who develop inhibitors. However, these treatment products are not always available in every country.

Non-factor replacement therapies are innovative treatment options for hemophilia that aim to rebalance hemostasis without the need for replacing the clotting factor that is missing. They target different points in the coagulation cascade, other than simply replacing the missing factor VIII (hemophilia A) or factor IX (hemophilia B). One non-factor replacement product approved in multiple countries as of publication (2022), is emicizumab, a bispecific antibody that mimics factor VIII in the clotting system. It is available for people with hemophilia A with and without inhibitors and is unique as it is dosed subcutaneously. Other non-factor replacement therapies are in the pipeline and may be available to patients in the future.

People with mild or moderate hemophilia A may sometimes use desmopressin (also called DDAVP) to treat minor bleeding. DDAVP is a synthetic hormone that stimulates the release of stored factor VIII from the vessels.

Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic drug that can be given as an additional therapy in pill form or by injection to help stop blood clots from breaking down. It is particularly useful for bleeding that involves mucous membranes such as those in the nose, mouth, or uterus. Epsilon aminocaproic acid is similar to tranexamic acid and comes in pills, liquid and can also be given by intravenous injection.

Cryoprecipitate and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) do not normally undergo viral inactivation procedures, meaning they often are less safe from viral contamination than CFC.

Cryoprecipitate is derived from blood and contains a moderately high concentration of clotting factor VIII (but not IX). It is effective for joint and muscle bleeds but is harder to store and administer. Cryoprecipitate can be made at local blood collection facilities.

In FFP, the red cells have been removed, leaving the blood proteins including clotting factors VIII and IX. It is less effective than cryoprecipitate for the treatment of hemophilia A because the factor VIII is less concentrated. Large volumes of plasma must be transfused, which can lead to a complication called circulatory overload.

Gene therapy is a promising treatment option for hemophilia. Instead of using CFCs to raise factor levels and prevent bleeds, hematologists may be able to use gene therapy to provide patients with a healthy copy of the defective gene. This means that an individual’s body could then produce enough clotting factor on its own to prevent bleeds and reduce the need for factor infusions. Several gene therapy products are in clinical trials, with at least one approved for use in PWH at the time of this publication (2022), and others expected to be approved in the near future.

There is no cure yet, but with treatment, people with hemophilia can live normal healthy lives. Without treatment, people with severe hemophilia may find it difficult to go to school or work regularly.

The standard of care today for people with severe hemophilia is prophylaxis. Prophylaxis is the regular administration (intravenously, subcutaneously, or otherwise) of factor or non-factor replacement treatment with the goal of preventing bleeding (especially life threatening or recurring joint bleeding) in PWH.

On-demand treatment is the administration of factor only when there is active bleeding. It is given for:

Additional treatment can be given before surgery, including dental work, or other activities that could cause bleeding. It is recommended that pregnant women with hemophilia have their factor VIII or IX levels tested prior to delivery, to determine if additional treatment is needed.

Small bruises are common in children with hemophilia, but they are not usually dangerous. However, bruises on the head might become serious, and should be checked by a hemophilia nurse or doctor.

Small cuts and scratches will bleed for the same amount of time as in a normal person. They are not usually dangerous.

Deeper cuts will often — but not always — bleed longer than normal. The bleeding can usually be stopped by putting direct pressure on the cut.

Nosebleeds can usually be stopped by putting pressure on the nose (above the nostrils) for a few minutes. Leaning forward will help the blood drain out of the nose and not into the throat. If bleeding is heavy or does not stop, treatment is needed.

| DOs | DON’Ts |

| Treat bleeding quickly! When you stop bleeding quickly, you have less pain and less damage to joints, muscles, and organs. Also, you need less treatment to control the bleeding. | Do not take ASA (acetylsalicylic acid, commonly know as Aspirin). ASA can cause more bleeding. Do not take ibuprofen, naproxen or blood thinners. Other drugs can affect clotting, too. Always ask your doctor which medicine is safe. |

| Stay fit. Strong muscles help protect you from joint problems and spontaneous bleeding (bleeding for no clear reason). Ask your hemophilia doctor or physiotherapist which sports and exercises are best for you. | Avoid injections into your muscles. A muscle injection could cause painful bleeding. However, vaccinations are important and safe for a person with hemophilia. Most other medications should be given by mouth or injected into the subcutaneous tissue or a vein rather than into a muscle. |

| See a hemophilia doctor or nurse regularly. The staff at a hemophilia clinic or treatment centre will give help and advice about managing your health. | |

| Take care of your teeth. To prevent problems, follow the advice of your dentist. Dental injections and surgery can cause major bleeding. | |

| Carry medical identification with information about your health. A special international medical card is available from the World Federation of Hemophilia. Some countries sell tags called “Medic-Alert” or “Talisman” that you wear around your neck or wrist. | |

| Learn basic first aid. Quick aid helps manage bleeding. Remember that very small cuts, scratches, and bruises are usually not dangerous. They do not usually need treatment. First aid is often enough. |

The most common type of hemophilia is called hemophilia A. This means the person does not have enough clotting factor VIII (factor eight).

A less common type is hemophilia B. This person does not have enough clotting factor IX (factor nine).

The result is the same for people with hemophilia A and B: they both bleed for a longer time than normal.

A person born with hemophilia will have it for life. The level of factor VIII or factor IX in the blood usually stays the same throughout the person’s life.

Hemophilia is quite rare. About 1 in 10,000 people is born with hemophilia A. About 1 in 50,000 people is born with hemophilia B.

Yes, there are several other factor deficiencies that also cause abnormal bleeding. These include deficiencies in factors I, II, V, VII, X, XI, XIII, and von Willebrand factor. The most severe forms of these deficiencies are even rarer than hemophilia A and B.

More information on von Willebrand disease, rare clotting factor deficiencies, and inherited platelet disorders.

The severity of hemophilia depends on the amount of factor VIII or factor IX in the blood.

There are three levels of severity: mild, moderate, and severe. People with severe hemophilia usually bleed frequently into their muscles or joints. They may bleed one to two times per week. Bleeding is often spontaneous, which means it happens for no obvious reason.

People with moderate hemophilia bleed less often, usually after an injury. Cases of hemophilia vary, however, and a person with moderate hemophilia can bleed spontaneously.

People with mild hemophilia usually bleed only as a result of surgery or major injury.

In rare cases, a person can develop hemophilia later in life. The majority of cases involve middle-aged or elderly people, or young women who have recently given birth or are in the later stages of pregnancy.

Acquired hemophilia is usually caused by the development of antibodies to factor VIII or factor IX: the body’s immune system destroys its own naturally produced factor VIII.

This condition often resolves with appropriate treatment.

For many years, people believed that only men could have symptoms of hemophilia and that women who “carry” the hemophilia gene do not experience symptoms themselves. We now know that many carriers do experience symptoms of hemophilia. As our knowledge about the disorder has increased, so has our understanding of why and how women can be affected. A woman who has less than 40 per cent of the normal level of clotting factor is no different from a man with the same factor levels—she has hemophilia. Some carriers have symptoms of hemophilia even though their clotting factor levels are above 40 per cent. A woman with levels of 40-60 per cent of the normal amount of clotting factor who experiences abnormal bleeding is called a symptomatic carrier.

Click here for more information on women and girls with hemophilia.

A carrier’s hematologist should be involved in the supervision of the pregnancy and should consult with the obstetrician before delivery. It is not necessary to perform prenatal diagnosis just for management of the pregnancy. This is only done if termination of pregnancy is being considered in the case of an affected child.

The factor VIII level (but not factor IX) tends to rise during pregnancy but should be checked sometime in the month or so before delivery.

A normal vaginal delivery is perfectly acceptable even if the fetus is male and at risk of hemophilia. Epidural anesthesia does not usually present a problem and is generally possible if the patient’s factor level is 40% or more. A cord blood sample after delivery will be used to check if a male baby has hemophilia.

Hemophilia is diagnosed by taking a blood sample and measuring the level of factor activity in the blood. Hemophilia A is diagnosed by testing the level of factor VIII coagulation activity in the blood. Hemophilia B is diagnosed by measuring the level of factor IX activity.

If the mother is a carrier, testing can be done before a baby is born. Prenatal diagnosis can be done at 9 to 11 weeks by chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or by fetal blood sampling at a later stage (18 or more weeks).

These tests can be done at a hemophilia treatment centre. Consult the Global Treatment Centre Directory for information on treatment centres around the world.

Most bleeding in hemophilia occurs internally, into the joints or muscles.

The joints that are most often affected are the knee, ankle, and elbow. Repeated bleeding without prompt treatment can damage the cartilage and the bone in a joint, leading to chronic arthritis and disability.

The most serious muscle bleeds are the iliopsoas muscle (the front of the groin area), the forearm, and the calf.

Some bleeds can be life-threatening and require immediate treatment. These include bleeds in the head, throat, gut, or iliopsoas.

Bruises are very common in children with hemophilia. A bruise is not usually cause for alarm, unless it is on the person’s head or neck, the person has a hard time moving, the bruise hurts, the lump in the bruise gets larger or does not go away, or if there is numbness or a tingling feeling along with the bruising. In any of these cases, a physician or local hemophilia treatment centre should be consulted.

People with hemophilia should not take aspirin (ASA or acetylsalicyclic acid), or anything containing aspirin, as well as other NSAIDs, because they interfere with the stickiness of platelets and can make bleeding problems worse. Paracetamol (acetominophen) is a perfectly safe alternative to aspirin to relieve pain.

A list of medications that can interfere with bleeding.

Some people with hemophilia avoid exercise because they think it may cause bleeds, but exercise can actually help prevent them. Strong muscles help protect someone who has hemophilia from spontaneous bleeds and joint damage.

Sport is an important activity for young people. It helps build muscle and develop mental concentration and coordination. However, some sports are riskier than others, and the benefits must be weighed against the risks. The severity of a person’s hemophilia should also be considered when choosing a sport. Sports like swimming, badminton, cycling, and walking are safe for most people with hemophilia, while American football, rugby, and boxing are usually not recommended.

Inhibitors are a serious medical problem that can occur when a person with hemophilia has an immune response to treatment with clotting factor concentrates.

Sometimes, a person’s immune system reacts to proteins in factor concentrates as if they were harmful foreign substances because the body has never seen them before. When this happens, inhibitors (also called antibodies) form in the blood to fight against the foreign factor proteins. This stops the factor concentrates from being able to fix the bleeding problem.

Bleeding is very hard to control in someone with hemophilia who develops inhibitors.

More information on inhibitors.

Prophylaxis is the regular use of clotting factor concentrates to prevent bleeds before they start. Injections of clotting factor are given one, two, or three times a week to maintain a constant level of factor VIII or IX in the bloodstream.

Prophylaxis can help reduce or prevent joint damage and improve the quality of life of people with hemophilia. In countries with access to adequate quantities of clotting factor concentrates, this is becoming the normal mode of treatment for younger patients, and can be started when the veins are well developed (usually between the ages of two and four years).

For more information on prophylaxis, click here.

A Port-a-Cath, or implantable venous access device (VAD), is a device that’s implanted under the skin, usually in the chest but sometimes in the arm. It has a reservoir connected to a catheter, which is then threaded into a vein. This way, medications and fluids can be injected easily, without having to find a vein for each injection.

VADs have made prophylaxis (regular infusions of factor concentrates) in hemophilia much easier for families. However, there are risks. Some studies have shown an infection rate as high as 50%. These infections can usually be treated with intravenous antibiotics but sometimes the device must be removed. There is also a risk of clots forming at the tip of the catheter. Like for any other procedure, each family must weigh the risks and benefits.

There is no cure for hemophilia. Gene therapy remains an exciting possibility and holds out the prospect of a partial or complete cure. There are many technical obstacles to overcome, but research currently underway is encouraging.

Technically, a liver transplant can cure hemophilia, since coagulation factors are produced by cells inside the liver. However, the risks of surgery and the requirement for lifelong medication to prevent rejection of the transplanted organ may outweigh the benefits.

The life expectancy of someone with hemophilia varies depending on whether they receive proper treatment. Without adequate treatment, many people with hemophilia die before they reach adulthood. However, with proper treatment, life expectancy for people with hemophilia is about 10 years less than that of males without hemophilia, and children can look forward to a normal life expectancy.

Source: WFH Guidelines for the Management of Hemophilia, 3rd edition (2020). For more detailed information about hemophilia, please refer to the guidelines at https://elearning.wfh.org/resource/treatment-guidelines/