Français / Español / 简体中文 / русский / العربية / 日本語

© 2026 World Federation of Hemophilia

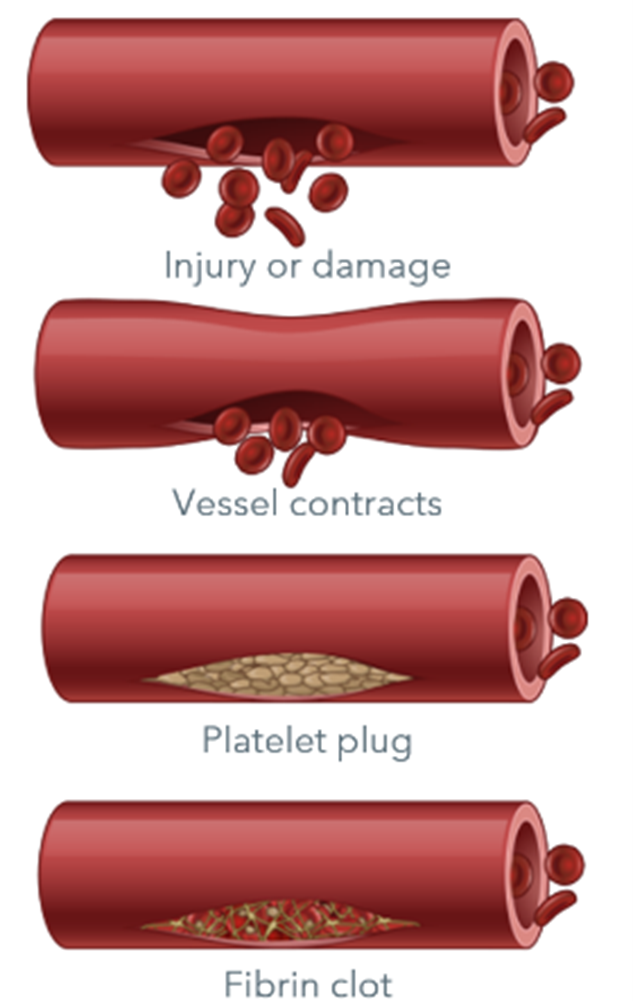

Clotting factors are proteins in the blood that control bleeding. When a blood vessel is injured, the walls of the blood vessel contract to limit the flow of blood to the damaged area. Then, small blood cells called platelets stick to the site of injury and spread along the surface of the blood vessel to stop the bleeding. At the same time, chemical signals are released from small sacs inside the platelets that attract other platelets to the area and make them clump together to form what is called a platelet plug.

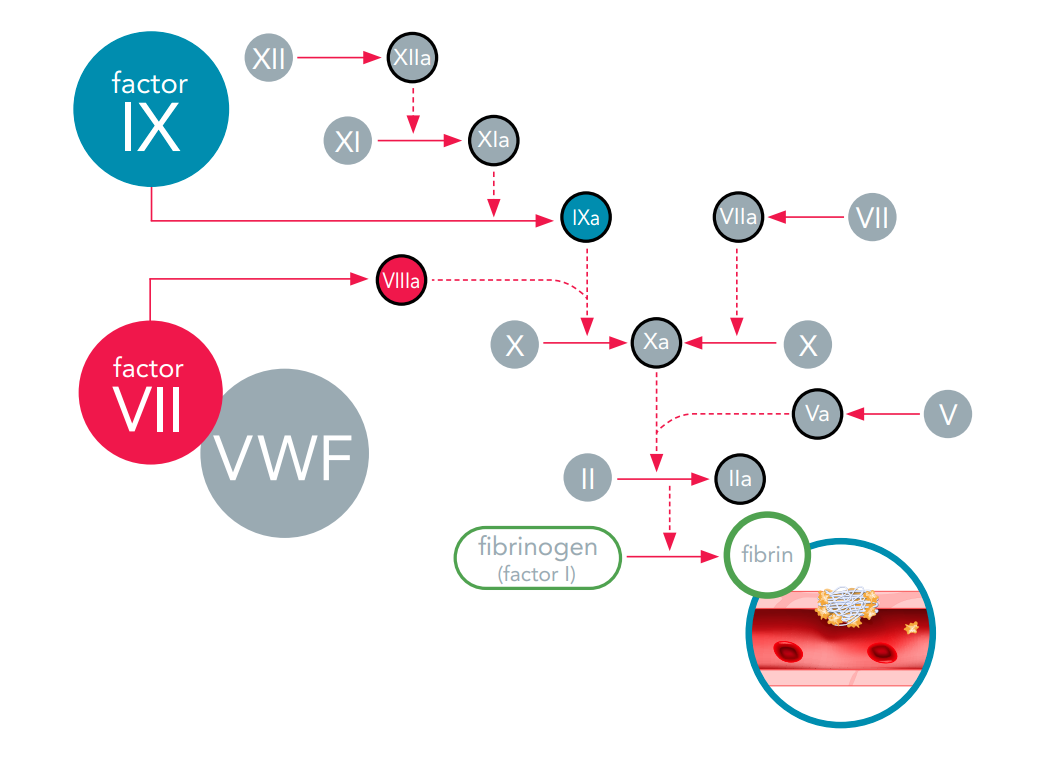

On the surface of these activated platelets, many different clotting factors work together in a series of complex chemical reactions (known as the coagulation cascade) to form a fibrin clot. The clot acts like a mesh to stop the bleeding.

Coagulation factors circulate in the blood in an inactive form. When a blood vessel is injured, the coagulation cascade is initiated, and each coagulation factor is activated in a specific order to lead to the formation of the blood clot. Coagulation factors are identified with Roman numerals (i.e., factor VIII or FVIII). The addition of the letter a (i.e., factor VIIIa) signifies the activated form of the clotting factor.

The coagulation cascade is a series of pathways that converge on factor X, a clotting factor essential for fibrin release and clot formation.

In people with a clotting factor deficiency, one (or very rarely, more than one) clotting factor is missing, present at a low level, or not working properly. This impacts the normal process of blood clotting, making it difficult for the blood to form a clot.

If any of the clotting factors are missing or are not working properly, the coagulation cascade is blocked. When this happens, the blood clot does not form, and the bleeding continues longer than it should.

Deficiencies of factor VIII and factor IX are known as hemophilia A and B, respectively. Deficiency or defect of von Willebrand factor (VWF) is known as von Willebrand disease (VWD). Rare clotting factor deficiencies are bleeding disorders in which one or more of the other clotting factors (i.e., factors I, II, V, V+VIII, VII, X, XI, XII, or XIII) is missing or not working properly. Less is known about these disorders because they are diagnosed so rarely. All factor deficiencies are rare diseases, and rare clotting factor deficiencies are considered ultra-rare diseases, because they affect even fewer people.

Humans have twenty-three pairs of chromosomes: twenty-two pairs of autosomal chromosomes (also called autosomes) and one pair of sex chromosomes (X or Y). Unlike hemophilia, which is due to mutations on the X chromosome, rare clotting factor deficiencies are due to mutations on the autosomes.

Factor I (fibrinogen) deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor I. Because the body produces less fibrinogen than it should, or because the fibrinogen is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form. Factor I deficiency is an umbrella term for several related disorders, known as congenital fibrinogen defects.

Afibrinogenemia is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child.

Hypofibrinogenemia, dysfibrinogenemia, and hypodysfibrinogenemia can be either recessive (both parents carry the gene) or dominant (only one parent carries and transmits the gene).

All types of factor I deficiency affect both males and females.

The symptoms of factor I deficiency differ depending on which form of the disorder a person has.

Given that fibrinogen is a central player of coagulation, the complete absence of fibrinogen leads to severe hemostatic defects, from life-threatening bleeding to thrombosis. Bleeding events are the most frequent symptoms – these are usually not predictable and can be severe and life-threatening hemorrhages.

People with afibrinogenemia may experience bleeding such as:

*Incidence of thrombotic events is higher in young children.

Symptoms are like those seen in afibrinogenemia. As a rule, the less factor I a person has in his/her blood, the more frequent and/or severe the symptoms.

Symptoms depend on how the fibrinogen (which is present in normal quantities) is functioning. Some people have no symptoms at all. Other people experience bleeding (like those seen in afibrinogenemia) and others show signs of thrombosis (abnormal blood clots in blood vessels) instead of bleeding.

Symptoms are variable and depend on the amount of fibrinogen that is produced and how it is functioning.

Factor I deficiency is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests, including a specific test that measures the amount of fibrinogen in the blood. However, low fibrinogen levels or abnormal function may be a sign of another disease, such as liver or kidney disorders, which should be ruled out before a bleeding disorder is diagnosed. Diagnostic tests should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre.

There are three treatments available for factor I deficiency. All are made from human plasma.

Treatment may also be given to prevent the formation of blood clots, as this complication can occur after fibrinogen replacement therapy.

Many people who have hypofibrinogenemia or dysfibrinogenemia do not need treatment. Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with factor I deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

Factor II (prothrombin) deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor II. Because the body produces less prothrombin than it should, or because the prothrombin is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form.

Factor II deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. Factor II deficiency is very rare.

Factor II deficiency may be inherited with other factors deficiencies (see “Combined deficiency of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors”). It can also be acquired later in life as a result of liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, or certain medications such as the blood-thinning drug warfarin. Acquired factor II deficiency is more common than the inherited form.

The symptoms of factor II deficiency are different for everyone. Generally, the less factor II a person has in his/her blood, the more frequent and/or severe the symptoms.

People with factor II deficiency may experience bleeding such as:

Factor II deficiency is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests. The doctor will need to test for prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin (aPTT). If both tests have prolonged time, then they will need to measure the blood level of factors I, II, V, VII, IX, and X. Diagnostic tests should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre.

There are two treatments available for factor II deficiency. Both are made from human plasma.

Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with factor II deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

Factor V deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor V. Because the body produces less factor V than it should, or because the factor V is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form.

Factor V deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. Factor V deficiency is very rare.

The symptoms of factor V deficiency are generally mild, and some people may experience no symptoms at all. However, children with a severe deficiency of factor V may bleed at a very young age. Some people with factor V deficiency have experienced bleeding in the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) very early in life.

People with factor V deficiency may experience bleeding such as:

Factor V deficiency is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests that should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre. The doctor will need to test for prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin (aPTT). If both tests have prolonged time, then they will need to measure the blood level of factors I, II, V, VII, IX, and X. People with abnormal levels of factor V should also have their factor VIII levels checked to rule out combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency, which is a completely separate disorder.

Treatment for factor V deficiency is usually only needed for severe bleeds or before surgery. Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or pathogen-reduced FFP is the usual treatment because there is no concentrate containing only factor V. Platelet transfusions, which contain factor V, are also sometimes an option.

Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with factor V deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

Combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by low levels of factors V and VIII. Because the amount of these factors in the body is lower than normal, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form. The combined deficiency is a completely separate deficiency from factor V deficiency and factor VIII deficiency (hemophilia A).

Combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. The deficiency is very rare, and very rarely, factor VIII deficiency could be inherited separately from only one parent.

In most cases, the disorder is caused by a single gene defect that affects the body’s ability to transport factor V and factor VIII outside the cell and into the bloodstream, and not by a problem with the gene for either factor.

The combination of factor V and factor VIII deficiency does not seem to cause more bleeding than if only one or the other of the factors were affected. The symptoms of combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency are generally mild.

People with combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency may experience bleeding such as:

Combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests to determine if the levels of both factors are lower than normal. These tests should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre.

There are three treatments available for combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency.

Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

Factor VII deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor VII. Because the body produces less factor VII than it should, or because the factor VII is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form.

Factor VII deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. Factor VII deficiency is very rare. Factor VII deficiency may be inherited with other factor deficiencies (see “Combined deficiency of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors”). It can also be acquired later in life as a result of liver disease, vitamin K deficiency, or certain medications such as the blood-thinning drug warfarin.

The symptoms of factor VII deficiency are different for everyone. As a rule, the less factor VII a person has in his/her blood, the more frequent and/or severe the symptoms. People with very low levels of factor VII can have very serious symptoms.

People with factor VII deficiency may experience bleeding such as:

Factor VII deficiency is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests that should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre.

There are several treatments available for factor VII deficiency.

Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with factor VII deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

Factor X deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor X. Because the body produces less factor X than it should, or because the factor X is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form.

Factor X deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. Factor X deficiency is one of the rarest inherited clotting disorders.

Factor X deficiency may also be inherited with other factor deficiencies (see “Combined deficiency of vitamin K-dependent clotting factors”).

Generally, the less factor X a person has in his/her blood, the more frequent and/or severe the symptoms. People with severe factor X deficiency can have serious bleeding episodes.

People with factor X deficiency may experience bleeding such as:

Factor X deficiency is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests that should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre.

There are three treatments available for factor X deficiency.

Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with factor X deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

Inherited combined deficiency of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (VKCFD) is a very rare inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X. To continue the chain reaction of the coagulation cascade, these four factors need to be activated in a chemical reaction that involves vitamin K. When this reaction does not happen the way it should, the clotting reaction is blocked and the blood clot does not form.

VKCFD is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. VKCFD is very rare.

VKCFD can also be acquired later in life as a result of disorders of the bowel, liver disease, dietary vitamin K deficiency, or certain medications such as the blood-thinning drug warfarin. Acquired VKCFD is more common than the inherited form. Some newborn babies have a temporary vitamin K deficiency, which can be treated with supplements at birth.

The symptoms of VKCFD vary a great deal from one individual to another but are generally mild. The first symptoms may appear at birth or not until later in life. Symptoms at birth must be differentiated from the acquired deficiency. People with severe deficiencies can have serious bleeding episodes, but the more serious symptoms are generally rare and only occur in those individuals with very low factor levels.

People with VKCFD may experience bleeding such as:

VKCFD is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests that should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre. Care should be taken, particularly in newborns, to exclude causes of acquired vitamin K deficiency or exposure to certain medications.

There are three treatments available for VKCFD.

Factor XI deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor XI. Because the body produces less factor XI than it should, or because the factor XI is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form.

Factor XI deficiency is also called hemophilia C. It differs from hemophilia A and B in that there is no bleeding into joints and muscles. Factor XI deficiency is the most common of the rare clotting factor deficiencies and the second most common bleeding disorder that impacts women (after von Willebrand disease).

Factor XI deficiency inheritance has an autosomal recessive pattern; however, some people have inherited factor XI deficiency when only one parent carries the gene. The disorder is most common in Ashkenazi Jews (Jews of Eastern European ancestry).

Most people with factor XI deficiency will have little or no symptoms at all. The relationship between the amount of factor XI in a person’s blood and the severity of his/her symptoms is unclear; people with only a mild deficiency in factor XI can have serious bleeding episodes. Symptoms of factor XI deficiency vary widely, even among family members, which can make it difficult to diagnose.

People with factor XI deficiency may experience bleeding such as:

Factor XI deficiency is diagnosed by a variety of blood tests that should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre.

There are several treatments available to help control bleeding in people with factor XI deficiency.

Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with factor XI deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

Factor XII deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor XII. Because the body produces less factor XII than it should, or because the factor XII is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form.

Factor XII deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. Factor XII deficiency is very rare.

Most people with factor XII deficiency do not experience many symptoms, even after major surgery. However, some experience poor wound healing.

Factor XII deficiency is often diagnosed accidentally during a routine coagulation blood test done prior to surgery or due to family history. Diagnosis is made by prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin (aPTT) tests, followed by a factor XII assay to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment is usually not needed for people with factor XII deficiency as symptoms are usually mild or non-existent. However, it is still important to notify health care providers or dental professionals before procedures.

Factor XIII deficiency is an inherited bleeding disorder that is caused by a problem with factor XIII. Because the body produces less factor XIII than it should, or because the factor XIII is not working properly, the clotting reaction is blocked prematurely, and the blood clot does not form.

Factor XIII deficiency is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means that both parents must carry the defective gene to pass it on to their child. It also means that the disorder affects both males and females. Factor XIII deficiency is very rare.

Most people with factor XIII deficiency experience symptoms from birth, often bleeding from the umbilical cord stump. Symptoms tend to continue throughout life. Generally, the less factor XIII a person has in his/her blood, the more frequent and/or severe the symptoms.

People with factor XIII deficiency may experience bleeding such as:

Factor XIII deficiency is difficult to diagnose. Standard blood clotting tests do not detect the deficiency, and many laboratories are not equipped with more specialized tests that measure the amount of factor XIII in a blood sample or how well factor XIII is working. Tests should be performed by a specialist at a hemophilia/bleeding disorders treatment centre. The high rate of bleeding at birth usually leads to early diagnosis.

There are several treatments available to help control bleeding in people with factor XIII deficiency.

Excessive menstrual bleeding in women with factor XIII deficiency may be controlled with antifibrinolytic drugs, or with hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) in women who do not wish to conceive.

For people with factor X deficiency, factor XIII deficiency, and afibrinogenemia, or who have a history of severe and frequent bleeds, it is recommended to use long-term prophylaxis. Prophylaxis is the regular administration (intravenously, subcutaneously, or otherwise) of a hemostatic agent with the goal of preventing bleeding (especially life-threatening bleeding or recurring joint bleeding).

Although the technology is available, there are no current trials or approved gene therapies for rare clotting factor deficiencies at the time of publication (2023).

As with all medications, these treatments may have side effects. People with rare clotting factor deficiencies should talk to their physician about possible side effects of treatment.

The antifibrinolytic drugs tranexamic acid and aminocaproic acid are used to hold a clot in place in certain parts of the body, such as the mouth, bladder, and uterus. They are also very useful in many situations, such as during dental work, but are not effective for major internal bleeding or surgery. Antifibrinolytic drugs are particularly useful for patients with factor XI deficiency. They are also used to help control excessive menstrual bleeding. Antifibrinolytic drugs can be administered orally or by injection. Antifibrinolytic drugs should be avoided for urinary bleeding.

When they are available, factor concentrates are the ideal and safest treatment for rare bleeding disorders. Unfortunately, individual concentrates are available only for factors I, VII, X, XI, and XIII. Factor concentrates for rare bleeding disorders are usually made from human plasma and are treated to eliminate viruses like HIV, and hepatitis B and C. Recombinant factor VIII and recombinant factor VIIa are also available. They are made in the laboratory and not from human plasma, so they carry no risk of infectious disease. Factor concentrates are administered intravenously.

This concentrate is made from human plasma and contains a mixture of clotting factors, including factors II, VII, IX, and X (however, some products do not contain all four factors). PCC is suitable for individual deficiencies of factor II and X as well as inherited combined deficiency of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (VKCFD). It is treated to eliminate viruses like HIV, and hepatitis B and C. Some PCCs have been reported to cause potentially dangerous blood clots (thrombosis). PCC is administered intravenously.

Plasma is the portion of blood that contains all the clotting factors, as well as other blood proteins. FFP is used to treat rare bleeding disorders when concentrates of the specific factor that is missing, are not available. FFP is the usual treatment for factor V deficiency. However, it usually does not undergo viral inactivation, so the risk of transmission of infectious diseases is higher. Viral-inactivated FFP is available in some countries and is preferable. Circulatory overload is a potential problem with this treatment: since the concentration of each coagulation factor in FFP is low, a large volume of it must be given over several hours to achieve an adequate rise in factor level. This large amount of FFP can overload the circulatory system and stress the heart. Other complications of treatment with FFP can occur, particularly allergic reactions or lung problems (transfusion-related lung injury [TRALI]). Risk of TRALI can be reduced by avoiding the transfusion of FFP collected from a previously pregnant female. These problems are much less common if viral-inactivated pooled FFP or pathogen-reduced FFP is used. FFP is administered intravenously.

Made from human plasma, cryoprecipitate contains factor VIII, fibrinogen (factor I), and a few other proteins important for blood clotting. Non-pathogen-reduced cryoprecipitate does not undergo viral inactivation and should only be used when factor concentrate is not available. Pathogen-reduced or viral-inactivated cryoprecipitate can be prepared by blood transfusion centers and should be used in the absence of CFCs. It contains higher concentrations of some (but not all) coagulation factors than FFP, so less volume is needed. It is only suitable for a few deficiencies. Cryoprecipitate is administered intravenously.

Desmopressin (DDAVP) is a synthetic hormone that raises the levels of factor VIII in patients with combined factor V and factor VIII deficiency. Since it is man-made, there is no risk of transmission of infectious diseases. Desmopressin has no effect on the levels of any of the other coagulation factors. It can be administered intranasally, intravenously, or subcutaneously.

Fibrin glue can be used to treat external wounds and during dental work, such as a tooth extraction. It is not used for major bleeding or surgery. It is applied directly to the bleeding site.

Platelets are small blood cells that are involved in the formation of blood clots and the repair of damaged blood vessels. Certain clotting factors, including factor V, are stored in small sacs inside platelets. Platelet transfusions are sometimes used to treat factor V deficiency.

Treatment with vitamin K (either in pill form or by injection) can help control symptoms of inherited combined deficiency of the vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (VKCFD). However, not everyone responds to this type of treatment. People who do not respond to vitamin K and have a bleed or need surgery will need factor replacement.

Hormonal contraceptives (such as birth control pills, or levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine device/system [IUD or IUS]) can help control menstrual bleeding in women who do not wish to conceive.

Learning you or your child has a bleeding disorder can be upsetting and you may experience a range of different emotions. For some people, it may cause fear and anxiety, while for others, being able to put a name to the symptoms they have been experiencing can be a tremendous relief. Parents may feel guilty to learn their child has inherited a genetic disease. All these feelings are normal and are likely to change over time as you learn more about the condition and the impact it will have on you or your family member’s life.

Talking to others—friends, parents, healthcare professionals, and other people with bleeding disorders—can be a great comfort. Learning as much as you can about the disorder will also help you feel more confident and relieve your fears. Get in touch with your local patient organization or bleeding disorder treatment centre to ask questions and discuss options. Patient groups and treatment centres can be located through the WFH website at wfh.org/find-local-support/.

People with bleeding disorders should be followed by a treatment centre that specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of bleeding disorders, as they are most likely to offer the best care and information.

A healthy diet and regular exercise keep the body healthy and strong. Exercise can also help reduce stress, anxiety, and depression, and reduce the frequency and severity of joint bleeds.

People with severe forms of bleeding disorders who are at risk of joint bleeds should avoid high-impact activities and sports such as football, wrestling, and skateboarding. Ideally, exercises should be prescribed for people with bleeding disorders by a skilled and experienced doctor or physiotherapist.

Good oral hygiene is essential to prevent tooth decay and gum disease. For people with bleeding disorders, maintaining good dental health is very important to reduce the need for dental surgery, which can be complicated by excessive or prolonged bleeding. People with bleeding disorders should:

Invasive procedures, such as scaling, extractions, or root canals, may cause bleeding in people with bleeding disorders. Even for minor procedures, the dentist should consult with the bleeding disorder treatment centre to determine the individual’s potential risk and to develop an appropriate plan to prevent or treat bleeding for any procedure. Medications may be needed before the procedure to prevent bleeding and ensure an uncomplicated procedure and recovery.

People with bleeding disorders should be vaccinated. Vaccines may need to be given subcutaneously (under the skin) rather than directly into the muscle to avoid the associated risk of bleeding, and this should be discussed with the clinician who looks after the bleeding disorder.

Vaccines against hepatitis A and B are particularly important for people that are treated with fresh frozen plasma and any other product that is not viral inactivated. Family members who assist with treatments should also be vaccinated, though this is less critical for those using viral-inactivated products.

Check all medications with your doctor. Some over-the-counter medications should be avoided because they interfere with clotting. People with bleeding disorders should not take aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen and naproxen) without medical advice.

People with bleeding disorders should always carry information about their disorder, the treatment required, and the name and telephone number of their physician or treatment centre. In emergencies, a medical alert bracelet or other identification, such as the WFH International Medical Card, notifies health care personnel of your bleeding disorder. Before traveling, find the address and telephone number of the bleeding disorder treatment centres at your destination(s) and take this information with you in case you need care. Treatment centres can be located on the WFH website (wfh.org/find-local-support/).

Women with clotting factor deficiencies may experience more symptoms than men because of the risk of bleeding associated with menstruation and childbirth. Girls may experience heavy bleeding when they begin to menstruate.

Women with clotting factor deficiencies may have heavier and/or longer menstrual flow, that may lead to iron deficiency (low levels of iron, which results in weakness and fatigue) and/or anemia (low levels of red blood cells).

Women with clotting factor deficiencies should receive genetic counseling about the risks of having an affected child well in advance of any planned pregnancies and should see an obstetrician as soon as they suspect they are pregnant. The obstetrician should work closely with the staff of the bleeding disorder treatment centre to provide the best care during pregnancy and childbirth, and to minimize the potential complications for both the mother and the newborn.

Women with certain factor deficiencies (such as factor X deficiency, factor XIII deficiency, and afibrinogenemia) may be at greater risk of miscarriage and placental abruption (a premature separation of the placenta from the uterus that disrupts the flow of blood and oxygen to the fetus). Therefore, these women require treatment throughout the pregnancy to prevent these complications.

The main risk related to pregnancy is postpartum hemorrhage. Bleeding disorders are associated with an increased risk of bleeding, both immediately after and for several weeks following delivery. Women with bleeding disorders should therefore work with their doctors (both the bleeding disorder specialist and the obstetrician) to develop an individual delivery plan. This plan should address all stages of labour, including delivery of the placenta, to reduce the risk and severity of bleeding. Treatment is different for each woman and depends on her personal and family history of bleeding symptoms, the diagnosis and severity of the bleeding disorder, and the mode of delivery. Women with bleeding disorders should be advised to contact their health care provider immediately if postpartum bleeding is excessive.

In some circumstances, infants born to women with bleeding disorders may also be at risk of inheriting the disorder and experience bleeding. Difficult and prolonged labour, and deliveries that require instrumentation, such as the use of forceps or vacuum extraction, should be avoided.