Français / Español / 简体中文 / русский / العربية / 日本語

© 2026 World Federation of Hemophilia

von Willebrand disease (VWD) is the most common inherited bleeding disorder, with a prevalence estimate between 1 in 100 and 1 in 10,000. Furthermore, 1 in 1,000 will have clinically significant bleeding symptoms that require medical attention. VWD affects both men and women equally, however women are more likely to seek medical help due to excessive menstrual bleeding (heavy periods) or bleeding around childbirth.

People with VWD have a problem with a clotting protein in their blood that helps control bleeding, known as the von Willebrand factor (VWF) protein. VWF carries the clotting protein Factor VIII (FVIII) to the site of injury and binds to the platelets in the blood vessel walls. This helps the platelets mesh together and form a clot to stop the bleeding. When there are lower levels of VWF, there will also be lower levels of FVIII, and clots will take a longer time to form. There are different types of VWD, all caused by a problem with the VWF protein — they either do not have enough VWF or it does not work the way it should.

Many people with VWD may not know that they have the disorder because they may not recognise their bleeding as abnormally heavy or prolonged. Bleeding can vary a lot between people with VWD, with some people experiencing little or no disruption to their lives unless they have serious injuries or surgery, and others experiencing a lot of disruption, even with less traumatic bleeds such as nosebleeds and menstrual bleeding. However, with all types of VWD, there can be bleeding problems.

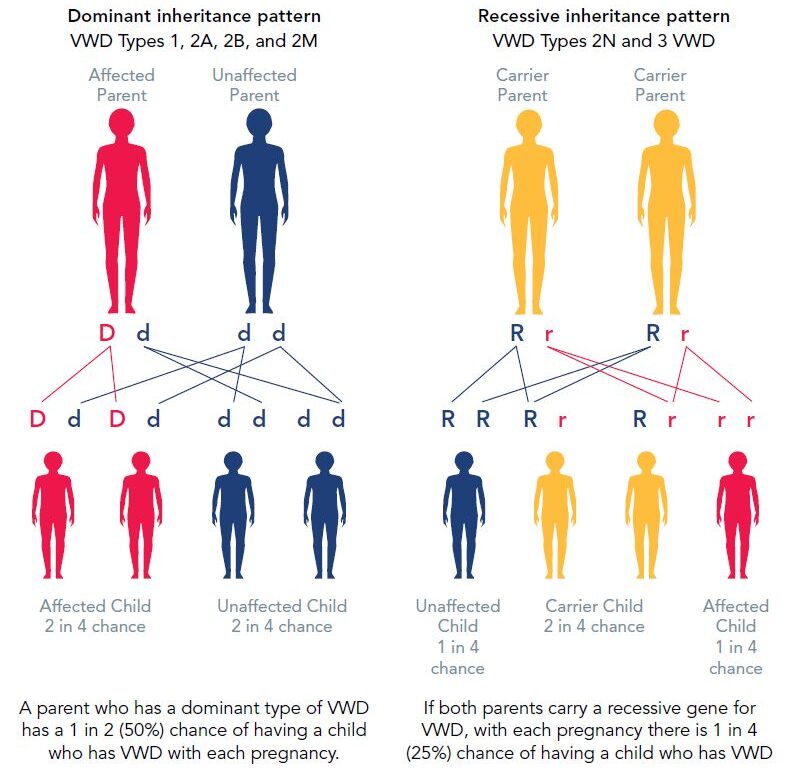

VWD is usually inherited, meaning it is passed down through the genes from either parent to a child of either sex. In this case there is usually evidence of a family history of bleeding problems, however, bleeding symptoms can vary a lot within a family. Sometimes there is no family history and VWD occurs due to a spontaneous change in the VWD gene before the baby is born. Some people can also acquire VWD later in life, which is known as acquired VWD.

Aging and some comorbidities are known to increase VWF levels, which may result in some people previously diagnosed with VWD to have normal VWF levels. However, the association between the increased VWF levels and bleeding symptoms is not established.

Inheritance of VWD

There are three main types of VWD, which require individualized treatment. Within each type of VWD, the disorder can be mild, moderate, or severe, however there is no standard severity system. Severity is determined by the use of bleeding assessment tools (BAT) together with lab tests, and it may change over the affected individuals’ lifetime. Bleeding symptoms can be quite variable within each type, depending in part on the VWF activity. Although how a person bleeds (bleeding phenotype) is more important than the type of VWD, it can be helpful to know which type of VWD a person has, because treatment and inheritance can differ for each type. For those where type remains unknown, it is still important to seek medical help for bleeding episodes.

Type 1 VWD is the most common form. People with type 1 VWD have lower than normal levels of VWF, ranging from slightly reduced, to very low levels. There is a subtype, type 1C, where VWF does not last as long in the body (meaning VWF has a shortened half-life).

Type 2 VWD involves a defect in the VWF structure, even if levels are normal. This means that VWF does not work properly, causing lower than normal VWF activity. There are different type 2 VWD subtypes:

Type 3 VWD is usually the most severe form, with very little or no VWF.

The main symptoms of VWD are:

People with VWD can have few or no symptoms. People with more serious VWD may have more bleeding problems. Symptoms can also change over time or with age. Usually, people with type 1 VWD (and mildly reduced levels) have mild symptoms, those with type 2 have moderate symptoms, and those with type 3 have severe symptoms. However, it is still possible for someone with any type to have serious bleeding or to experience bleeding that affects their quality of life.

Sometimes VWD is discovered only when there is heavy bleeding after a serious accident, dental or surgical procedure, or childbirth. Your doctor should use validated BATs to evaluate the severity of your bleeding and provide treatment plan which best suits your medical condition and your lifestyle.

More women than men show symptoms of VWD. Women with VWD often bleed more or longer than normal with menstruation (periods) and following childbirth.

Blood type can play a role. Some studies have shown that people with type O blood often have lower levels of VWF than people with types A, B, or AB. Irrespective of your blood group, if you are diagnosed with VWD, your treatment is the same.

If your doctor suspects that you have a bleeding disorder, various tests can be performed after evaluation of symptoms using BATs. To minimize delay of diagnosis, which sometimes extends to 15 or more years, it is important to see a hematologist who specializes in bleeding disorders and has access to good laboratories. Testing can be done at a bleeding disorders treatment centre.

Testing involves measuring a person’s level and activity of VWF and FVIII. VWD cannot be diagnosed with routine blood tests.

Testing is often repeated because a person’s VWF and FVIII levels can vary at different times and may be elevated during times of stress, such as when anemic, or during a bleeding event like menstrual bleeding. If you are on a birth control pill, you should discuss with your provider as high dose versions may elevate your VWF levels making it more difficult to diagnose. Women should be tested at different points in their cycle to get the most accurate reading.

Some of the tests that may be performed include:

| Test | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) | Measures how long it takes for bleeding to stop |

| Factor VIII clotting activity | Measures how well factor VIII works |

| von Willebrand factor antigen | Measures the amount of VWF in the blood |

| Ristocetin co-factor and/or collagen binding activity | Measures how well VWF works |

| von Willebrand factor multimers | Looks at the structure and pattern of VWF |

To determine the type of VWD, such as for inheritance patterns or potential treatments, ask your doctor to refer you for genetic testing. In some countries, genetic testing is available and will provide the most accurate answer and can help your doctor select the most appropriate treatment.

Treatments for VWD aim to help stop bleeding by improving blood clotting (tranexamic acid or aminocaproic acid) or increasing your plasma VWF levels (desmopressin or VWF concentrates). The type of treatment depends in part on the type of VWD a person has, the amount of VWF they have, and the severity of bleeding and/or planned surgery. People with mild forms of VWD often do not require treatment for the disorder except when undergoing surgery or dental work.

When to call your treatment centre?

Desmopressin (also called DDAVP) works by causing your body to release its stores of VWF, which raises the plasma levels of VWF and FVIII to help blood clot. DDAVP is inexpensive and easy to handle, and can be injected or taken by nasal spray. However, it does not work for everyone. A doctor needs to test to find out if an individual responds to DDAVP, ideally before treatment is needed, which can also help determine what type of VWD a person has. DDAVP is generally effective for treating type 1 VWD, and helps prevent or treat bleeding in some forms of type 2 VWD. It is generally not used in type 1C VWD as the response will only last a short time, nor in type 3 VWD, as no response to desmopressin is seen.

DDAVP is used to control bleeding in an emergency or during surgery. DDAVP can cause dizziness, flushing, or palpitations, which may improve if it is given more slowly. Factor concentrates are used when DDAVP is not effective or when there is a high risk of major bleeding. DDAVP is generally not recommended in people with active cardiovascular disease, seizure disorders, children less than 2 years of age, and in those with type 1C VWD who are undergoing surgery. DDAVP should not be given for more than 3 consecutive days.

There are two types of VWF-containing concentrates. The first type is “plasma derived” that is purified from blood. These concentrates contain VWF and varying amounts of FVIII. The other type is “recombinant”, a version of VWF that is made in a laboratory and is not obtained from blood donation. These concentrates are the preferred treatment for type 3 VWD, most forms of type 2 VWD, and for serious bleeding or major surgery in all types of VWD.

Bleeding in mucous membranes (inside the nose, mouth, intestines, or womb) can be controlled by drugs such as tranexamic acid, aminocaproic acid, or fibrin glue. These products are used to maintain a clot, and do not actually help form a clot.

Hormone treatment, such as oral contraceptives, can be an option for some women and girls with VWD. These hormonal drugs help to reduce heavy menstrual bleeding and can also prevent pregnancy. In women who are not planning to become pregnant, an intrauterine device (IUD) may be a good option to help control heavy periods as it can last up to five years. In women with heavy periods who are trying to have a baby, hormone treatments cannot be used. Antifibrinolytic agents, DDAVP, or VWF concentrates may be effective for treating heavy menstruation.

In people with VWD who have a history of severe and frequent bleeds, it is recommended to use long-term prophylaxis with a VWF concentrate. Prophylaxis is the regular administration (intravenously, subcutaneously, or otherwise) of a hemostatic agent with the goal of preventing bleeding (especially life-threatening bleeding or recurring joint bleeding).

As with all medications, these treatments may have side effects. People with VWD should talk to their physician about possible side effects of treatment.

Women with VWD tend to have more symptoms than men because of menstruation (periods) and childbirth. Girls with VWD may have especially heavy bleeding when they begin to menstruate. Women with VWD often have heavier and/or longer periods. This heavier menstrual flow can cause iron deficiency, which if untreated, can cause anemia.

Why are iron levels important?

Low iron can cause vague symptoms such as weakness and fatigue, and is very common in women with VWD. Women with VWD should be checked regularly for low iron levels (using a ferritin test) as well as for anemia (by checking hemoglobin levels). If iron levels are low, iron tablets should be taken to boost iron levels and prevent anemia. At the same time, the cause of the bleeding (for example heavy periods) should be treated or else iron levels will fall again.

What is “excessive” bleeding?

Every woman is different, and what is considered “normal” for one woman may be “excessive” for another. The average amount of blood lost during a “normal” period is 30–40 ml. Blood loss of 80 ml or more is considered heavy. As measuring your period is not practical, common signs of heavy periods to look out for are:

Of course, the amount of blood lost can be difficult to measure. If you believe you may suffer from excessive bleeding, complete a bleeding assessment chart during your next period. This is only a guide, but it can be a useful tool for you and your doctor to use when assessing your menstrual flow.

A woman with VWD should inform her treatment centre if she is planning a fertility treatment, as treatment to boost VWF levels may be needed for some fertility procedures.

A woman with VWD should see an obstetrician as soon as she suspects she is pregnant. The obstetrician should work with a bleeding disorders treatment centre to provide the best care during pregnancy and childbirth. During pregnancy, women without VWD experience an increase in VWF and FVIII levels. For women with VWD, this increase will vary (improvement for some women with type 1 VWD, no improvement in how VWF works for women with type 2 VWD, and no change for those with type 3 VWD). For those who see an improvement in levels, these clotting factor levels fall quickly after delivery, and bleeding can continue for longer than normal. Therefore, checking factor levels during pregnancy to diagnose VWD may not be accurate.

After the baby is born, it is normal to experience period-type bleeding that will improve over a number of weeks as the womb heals and returns to normal. It is not normal to bleed longer than 6 weeks or to experience the heavy bleeding signs above (such as changing pads/tampons more frequently than 2 hourly or passing clots larger than a pecan). If these occur, you may need treatment to boost your VWF levels and you should contact your local treatment centre. To prevent prolonged bleeding after childbirth, many women with VWD now receive tranexamic acid tablets to take for the first 2 weeks after delivery.

Women with VWD entering menopause (end of menstruation, usually between the ages of 45 and 50) are at increased risk of unpredictable and heavy bleeding, even if their periods were previously normal. Again, hormonal treatment, iron tablets, and tranexamic acid can all be helpful in this instance. It is important for a woman with VWD to maintain a strong relationship with her gynecologist as she approaches menopause and to discuss with her treatment centre if her bleeding worsens.

VWD is the most common type of bleeding disorder. People with VWD have a problem with a protein in their blood called von Willebrand factor (VWF) that helps control bleeding. When a blood vessel is injured and bleeding occurs, VWF helps cells in the blood, called platelets, mesh together and form a clot to stop the bleeding. People with VWD do not have enough VWF, or it does not work the way it should. It takes longer for blood to clot and for bleeding to stop.

In 1926, Dr. Erik von Willebrand, a Finnish physician, published the first description of an inherited bleeding disorder that was different from hemophilia. Dr. von Willebrand’s studies into this new disease began with a family living on the island of Föglö in the Åland archipelago in the Baltic Sea. One of the women (the first known sufferer of VWD) in this family bled to death in her teens from menstrual bleeding, and four other family members had also died before her as a result of uncontrolled bleeding.

It is estimated that up to 1% of the world’s population suffers from VWD, but because many people have only very mild symptoms, only a small number of them know they have it. Research has shown that as many as 9 out of 10 people with VWD have not been diagnosed.

VWD is usually inherited. It is passed down through the genes from either parent to a child of either sex. Occasionally, VWD occurs due to a spontaneous change in the VWD gene before the baby is born.

A woman with VWD has a 50% chance of passing the disease on to her child. If the father has VWD, the child still has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease.

VWD and hemophilia are different types of bleeding disorders. VWD is caused by a problem with von Willebrand factor, whereas hemophilia is caused by a problem with another type of clotting factor (factor VIII in hemophilia A; factor IX in hemophilia B). Though both disorders are usually inherited, the inheritance pattern (the way the genes are passed down from parent to child) is different. Symptoms of VWD are usually milder than symptoms of hemophilia, but serious bleeding episodes can occur in either condition.

The severity of symptoms depends partly on the type of VWD a person has. Types 1 and 2 are generally mild, but people with Type 3 VWD can have very serious bleeding episodes. Even within each type of VWD, though, symptoms can be quite variable.

More women than men show symptoms of VWD because of menstruation and childbirth. Women with VWD often bleed more or longer than normal with their monthly periods. However, men can also have serious symptoms, especially those with Type 3 VWD.

No. There are many possible reasons for heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia) besides VWD. However, one British study showed that one out of every five women who went to the doctor because of heavy or prolonged bleeding actually had a bleeding disorder.

VWD is diagnosed through a series of blood tests that should be performed by specialists at a bleeding disorder treatment centre. Several different tests need to be done in order to determine the exact type of VWD a person has.

The diagnosis of VWD is difficult. Research has shown that as many as 9 out of 10 people with VWD have not been diagnosed.

Yes. Most women with VWD have no problem conceiving. Women with VWD should consult an obstetrician as soon as they learn they are pregnant. The obstetrician will work with the bleeding disorders treatment centre to provide the best care during the pregnancy and childbirth.

Women with Type 3 VWD seem to have more frequent miscarriages, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy. However, it is possible that these miscarriages are simply more noticeable in women with VWD, because there is more bleeding. Bleeding after miscarriage can also be more severe for women with VWD.

Yes. The hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for all people who routinely receive blood or blood products, even though the risk of transmission is very small. People with VWD, especially those who also have hepatitis C, should also get vaccinated against hepatitis A. In very rare cases, hepatitis A has also been transmitted by blood products.

No, there is no cure for VWD. It is a lifelong condition, but there are safe, effective treatments for all types of VWD.

Source: ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of VWD (2021). For more detailed information about prophylaxis, please refer to the guidelines at https://elearning.wfh.org/resource/ash-isth-nhf-wfh-guidelines-on-the-diagnosis-and-management-of-vwd/

© 2026 World Federation of Hemophilia