Français / Español / 简体中文 / русский / العربية / 日本語

© 2025 World Federation of Hemophilia

Гемофилия — это болезнь кровотечений. У людей с гемофилией кровь течет не быстрее, чем обычно, но кровотечения длятся дольше, потому что в их крови недостаточно определенных факторов свертывания. Фактор свертывания крови — это белок крови, регулирующий процесс кровотечения.

Гемофилия считается редким заболеванием. Наиболее распространенный ее тип — гемофилия А. В этом случае в крови недостаточно фактора свертывания VIII (фактор восемь). На каждые 100 000 мужчин примерно 21 болен гемофилией А. Менее распространенный тип заболевания называется гемофилия В. У людей, страдающих гемофилией В, в крови недостаточно фактора свертывания IX (фактор девять). Из 100 000 мужчин четыре человека имеют гемофилию B. Но для людей с гемофилией A и B течение заболевания одинаково: кровотечение у них длится дольше, чем обычно.

В течение многих лет люди считали, что симптомы гемофилии, такие как кровотечение в целом и особенно кровотечение в суставы, могут быть только у мужчин и мальчиков (или юношей), и что женщины, «несущие» ген гемофилии, сами не испытывают симптомов кровотечения. Теперь мы знаем, что многие женщины и девочки действительно испытывают симптомы гемофилии.

Люди уже рождаются с этим заболеванием. Ею нельзя заразиться как простудой.

Гемофилия — наследственное заболевание, которое передается от родителей к детям на генетическом уровне. Гены содержат информацию о том, как будут развиваться клетки организма по мере взросления человека. Так, например, именно гены ответственны за цвет волос или глаз.

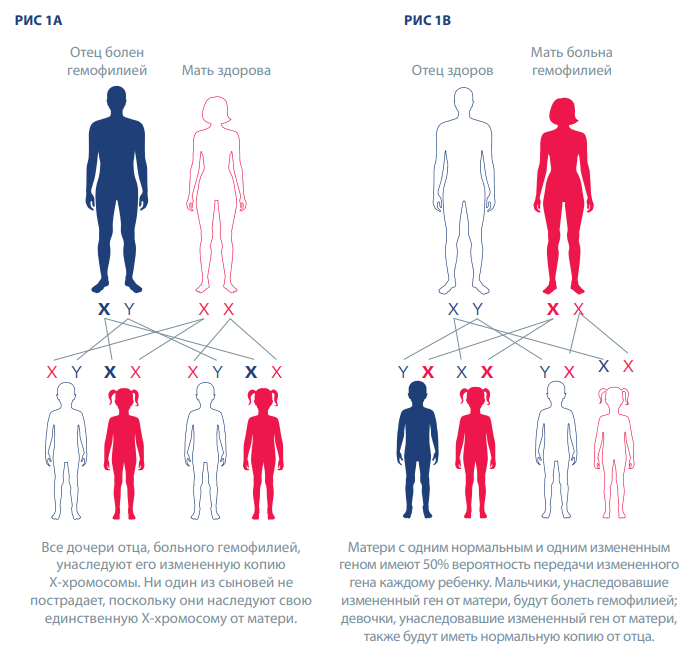

Ген гемофилии передается от родителей к детям. Гены гемофилии А и В расположены в Х-хромосоме, и поэтому гемофилию называют X-сцепленным заболеванием.

Все дочери отца, больного гемофилией, унаследуют его измененную копию Х-хромосомы. Ни один из сыновей не пострадает, поскольку они наследуют свою единственную Х-хромосому от матери (рис. 1А).

Матери с одним нормальным и одним измененным геном имеют 50% вероятность передачи измененного гена каждому ребенку (рис. 1B). Мальчики, унаследовавшие измененный ген от матери, будут болеть гемофилией; девочки, унаследовавшие измененный ген от матери, также будут иметь нормальную копию от отца. В среднем у женщин и девочек с геном гемофилии количество фактора свертывания крови составляет около 50% от нормы, но у некоторых уровень фактора свертывания крови намного ниже, и у них могут проявляться признаки гемофилии. По оценкам, на каждого мужчину, больного гемофилией, приходится в среднем три родственницы.

Иногда гемофилия может возникать у людей, в семейном анамнезе которых ее раньше не было, например из-за спонтанных генетических мутаций. В этих случаях болезнь вызвана изменением собственных генов человека.

В редких случаях гемофилия может развиться в более позднем возрасте. Это так называемая приобретенная гемофилия — аутоиммунное заболевание, а не наследственное нарушение свертываемости крови. В большинстве таких случаев речь идет о людях среднего или пожилого возраста, а также молодых женщинах, которые недавно родили ребенка или находятся на поздних сроках беременности. Это состояние не передается по наследству и часто проходит при соответствующем лечении.

Под тяжестью заболевания подразумевается то, насколько серьезно протекает болезнь. По форме тяжести различают три степени гемофилии, обусловленные уровнем фактора свертывания крови, который измеряется в процентах от нормальной активности фактора в крови или в количестве международных единиц (МЕ) на миллилитр (мл) цельной крови. Нормальный диапазон факторов свертывания VIII или IX в крови составляет от 40 до 150 %. Людям с уровнем активности фактора менее 40 % диагностируют гемофилию (см. таблицу 1). Тем не менее у некоторых людей характер кровотечений не соотносится с установленным уровнем активности фактора. В этих случаях при принятии решения о вариантах лечения фенотип заболевания (симптомы кровотечения) более важен, чем уровень активности фактора.

Таблица 1

| Степень тяжести | Уровень фактора свертывания крови | Кровотечения |

|---|---|---|

| Гемофилия легкой формы |

От 5 до < 40 % от нормального уровня (или 0,05–0,40 МЕ/мл) |

|

| Гемофилия средней формы |

От 1 до 5 % от нормального уровня (или 0,01–0,05 МЕ/мл) |

|

| Гемофилия тяжелой формы |

< 1 % от нормального уровня (или 0,01 МЕ/мл) |

|

*На основании материалов таблицы 2-1 руководства WFH по лечению гемофилии, 3‑е издание.

Симптомы гемофилии типов А и В одинаковы. Среди них:

Кровоизлияние в сустав или мышцу вызывает:

Примерно у одной трети женщин с гемофилией уровень фактора свертывания крови составляет менее 60% от нормы, и у них могут наблюдаться аномальные кровотечения. В большинстве случаев они испытывают симптомы, схожие с теми, которые наблюдаются у мужчин с легкой формой гемофилии, а также некоторые специфические для женщин, такие как длительные или обильные менструальные кровотечения, а также повышенная вероятность послеродовых кровотечений после родов.

Таблица 2. Места возникновения кровотечений при гемофилии

| Серьезное состояние |

|

| Угроза для жизни |

|

*На основании материалов таблицы 2-2 руководства WFH по лечению гемофилии, 3‑е издание.

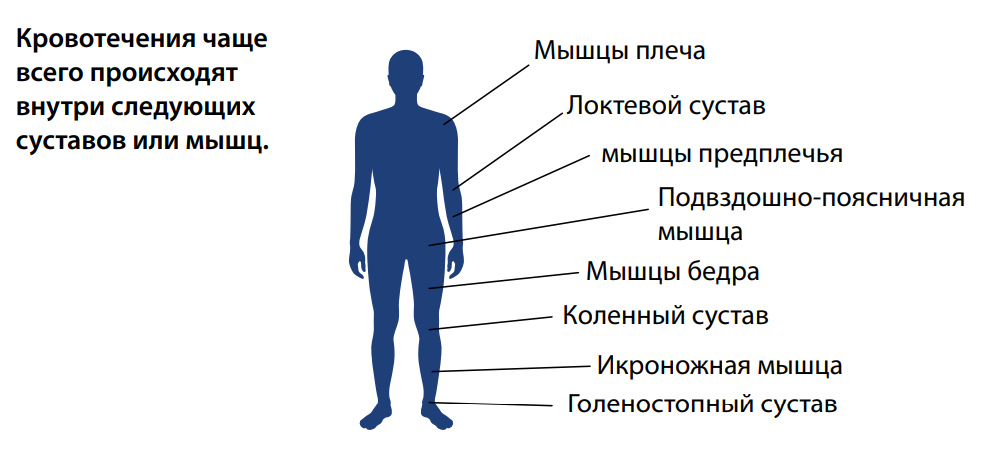

У больных гемофилией могут возникать внутренние и наружные кровотечения. В большинстве случаев при гемофилии происходят внутренние кровоизлияния в мышцы или суставы. Чаще всего поражаются голеностопные суставы, колени и локти. Внутримышечные кровотечения в большинстве случаев затрагивают мышцы плеча и предплечья, подвздошно-поясничную группу мышц (сгибатели бедра), мышцы бедра и голени.

Многократное кровоизлияние в один и тот же сустав может стать причиной воспаления и болей. Повторяющееся кровотечение может спровоцировать возникновение других проблем, например артрита, вызывая боль и затрудняя ходьбу или выполнение простых действий. При этом — в отличие от некоторых видов артрита — суставы кистей рук при гемофилии обычно не поражаются.

У новорожденных и детей раннего возраста с тяжелой формой гемофилии наиболее частыми видами кровотечений являются:

Поскольку большинство кровотечений происходит, когда больной находится вне центров лечения гемофилии, важно, чтобы и больные, и лица, осуществляющие уход за ними, были проинформированы:

Гемофилия диагностируется путем взятия образца крови и измерения уровня активности фактора свертывания в крови. Гемофилия А диагностируется путем определения уровня активности фактора VIII. Гемофилия B диагностируется путем измерения уровня активности фактора IX.

Пренатальную диагностику можно провести, взяв небольшой образец из плодной части плаценты (биопсия ворсин хориона) на ранних сроках беременности или кровь у плода (амниоцентез на поздних сроках беременности) на более поздних сроках. Также может быть выполнен анализ пуповинной крови.

Анализы проводятся в центрах лечения гемофилии.

Современные методы лечения гемофилии очень эффективны. При достаточном приеме лечебных препаратов и надлежащем уходе больные гемофилией могут жить совершенно обычной жизнью. Без лечения большинство детей с тяжелой формой гемофилии умирают в юном возрасте. По текущим оценкам, около 800 000 человек во всем мире больны гемофилией, но многие из них не получают адекватного лечения. Всемирная федерация гемофилии делает все возможное, чтобы это изменить.

Концентраты фактора свертывания крови со стандартным и удлиненным периодом полувыведения для внутривенных инъекций являются важным методом лечения гемофилии. Они могут быть созданы на основе человеческой крови (так называемые продукты переработки плазмы крови) или произведены с использованием генно-инженерных клеток, несущих ген человеческого фактора (рекомбинантные продукты). Факторные концентраты изготавливаются на высокотехнологичных производственных предприятиях. Все имеющиеся в продаже концентраты факторов сегодня специальным образом обрабатываются для удаления или инактивации передающихся через кровь вирусов. Концентраты факторов свертывания крови с удлиненным периодом полувыведения сохраняются в организме дольше. Они были специально разработаны для профилактического лечения гемофилии и поддержания более высоких уровней факторов свертывания крови для предотвращения кровотечений.

Агенты обходного действия, такие как концентраты активированного протромбинового комплекса и рекомбинантный активированный фактор VIIa (rFVIIa), используются для лечения острых кровотечений у больных гемофилией A или B при развитии ингибитора. Однако подобные лекарственные препараты доступны не всегда и не во всех странах.

Препараты, не относящиеся к заместительной терапии факторами свертывания, — это инновационный подход к лечению гемофилии, направленный на восстановление баланса гемостаза без необходимости замены отсутствующего фактора свертывания крови. Такие препараты «нацелены» на разные фазы коагуляционного каскада вместо простой замены отсутствующего фактора VIII (гемофилия А) или фактора IX (гемофилия В). Одним из препаратов, не относящихся к заместительной терапии факторами свертывания и одобренных во многих странах на момент публикации (2022 г.), является эмицизумаб. Это биспецифическое антитело, которое имитирует фактор VIII в системе свертывания крови. Он доступен для людей с гемофилией А с ингибиторами и без них и уникален тем, что вводится подкожно. Другие виды терапии, не относящиеся к заместительной терапии факторами свертывания, находятся в стадии разработки и могут стать доступны для пациентов в будущем.

Люди с гемофилией А легкой или средней степени тяжести могут иногда использовать десмопрессин (также называемый DDAVP) для лечения незначительных кровотечений. DDAVP представляет собой синтетический гормон, который стимулирует высвобождение депонированного фактора VIII из сосудов.

Транексамовая кислота — это антифибринолитическое средство в форме таблеток или в виде инъекций, которое можно назначать в качестве дополнительной терапии, чтобы предотвратить разрушение кровяных сгустков. Данный препарат особенно хорошо действует при кровотечениях, затрагивающих слизистые оболочки, например носа, рта или матки. Эпсилон-аминокапроновая кислота аналогична транексамовой и выпускается в виде таблеток, в жидкой форме и в форме раствора для внутривенного введения.

Криопреципитат и свежезамороженная плазма обычно не проходят процедуру вирусной инактивации, а значит, они часто не так безопасны в плане вирусного заражения, как концентраты факторов свертывания крови.

Криопреципитат, получаемый из крови, содержит умеренно высокую концентрацию фактора свертывания крови VIII (но не IX). Он эффективен при суставных и мышечных кровотечениях, но его сложнее хранить и вводить. Криопреципитат можно приготовить на местных станциях сбора крови.

В случае со свежезамороженной плазмой после удаления эритроцитов в ней остаются белки крови, включая факторы свертывания VIII и IX. Она менее эффективна, чем криопреципитат для лечения гемофилии А, поскольку фактор VIII имеет меньшую концентрацию. При использовании плазмы приходится переливать большие объемы, что может привести к осложнению, называемому циркуляторной перегрузкой.

Генная терапия является перспективным методом лечения гемофилии. Вместо того чтобы использовать концентраты факторов свертывания крови для повышения их уровня в крови и предотвращения кровотечений, гематологи когда-нибудь смогут прибегать к генной терапии, чтобы заменить дефектный ген его здоровой копией. Это означает, что организм человека будет самостоятельно производить достаточное количество фактора свертывания, предотвращая кровотечения и сокращая потребность организма в дополнительном введении фактора. В настоящий момент клинические испытания проходят несколько препаратов для генной терапии, и по крайней мере один из них одобрен для использования у людей с гемофилией на момент публикации данного материала (2022 г.). Другие, как ожидается, будут одобрены в ближайшем будущем.

Лекарство от гемофилии пока не нашли, но при правильном лечении люди с гемофилией могут жить нормальной здоровой жизнью. Без соответствующего лечения людям с тяжелой формой гемофилии трудно регулярно ходить в школу или работать.

В настоящее время стандартом лечения больных с тяжелой формой гемофилии является профилактика. Профилактика — это регулярное введение (внутривенно, подкожно или иным образом) препаратов факторов или препаратов, не относящихся к заместительной терапии факторов свертывания, с целью предотвращения кровотечения (особенно угрожающего жизни или рецидивирующего суставного кровотечения) у людей с гемофилией.

Лечение по необходимости — это введение фактора только при наличии сильного кровотечения. К такому виду лечения прибегают в случае:

Перед операциями пациентам может быть назначено дополнительное лечение, в том числе лечение зубов или другие виды вмешательств, которые могут вызвать кровотечение. Беременным женщинам с гемофилией рекомендуется проверять уровень фактора VIII или IX перед родами, чтобы определить, требуется ли им дополнительное лечение.

Часто у детей с гемофилией появляются небольшие синяки, но обычно они неопасны. Тем не менее синяки в области головы могут иметь серьезные последствия, поэтому в таком случае стоит проконсультироваться с медсестрой или врачом.

Небольшие порезы и царапины будут кровоточить столько же времени, сколько и у обычного человека. Обычно они неопасны.

Более глубокие порезы часто, но не всегда, кровоточат дольше, чем обычно. Кровотечение в большинстве случаев можно остановить, надавив на порез.

Носовое кровотечение обычно можно остановить, надавливая на нос (над ноздрями) в течение нескольких минут. Наклон вперед поможет крови вытекать из носа, не попадая в горло. Если кровь идет очень сильно или не останавливается, необходимо начинать лечение.

| Рекомендуется | Не рекомендуется |

| Сразу же начинайте лечение! Быстро останавливая кровотечение, вы можете избежать боли и повреждений суставов, мышц и органов в дальнейшем. Кроме того, вам потребуется меньше лекарств, чтобы остановить кровотечение. | Не принимайте ацетилсалициловую кислоту (обычно знакомую нам как аспирин). Ацетилсалициловая кислота может спровоцировать усиление кровотечения. Не принимайте ибупрофен, напроксен или препараты для разжижения крови. Другие лекарства также могут влиять на свертываемость крови. Всегда уточняйте у своего врача, какое лекарство безопасно для вас. |

| Поддерживайте хорошую физическую форму. Сильный мышечный корсет защищает от проблем с суставами и спонтанных кровотечений (кровотечения без ясной причины). Уточните у врача, который лечит вас от гемофилии, или физиотерапевта, какие виды спорта и упражнения лучше всего подходят для вас. | Избегайте внутримышечных инъекций. Внутримышечные инъекции могут стать причиной болезненных кровотечений. Тем не менее прививки нужны людям с гемофилией и безопасны для них. Большинство других лекарств следует давать перорально, внутривенно или вводить в подкожную клетчатку, а не в мышцу. |

| Регулярно консультируйтесь с лечащим врачом или медсестрой. Персонал клиники гемофилии или лечебного центра окажет вам помощь и проконсультирует по вопросам здоровья. | |

| Позаботьтесь о своих зубах. Чтобы избежать проблем, следуйте советам своего стоматолога. Стоматологические инъекции и операции могут спровоцировать сильное кровотечение. | |

| Носите при себе медицинскую книжку с информацией о вашем здоровье. Обратившись во Всемирную федерацию гемофилии, вы можете получить специальную медицинскую карту международного образца. В некоторых странах продаются карточки больного, называемые Medic-Alert или Talisman, которые носятся на шее или запястье. | |

| Изучите основы оказания первой помощи. Быстрая помощь помогает справиться с кровотечением. Помните, что маленькие порезы, царапины и синяки обычно неопасны и не нуждаются в лечении. Часто бывает достаточно оказать первую помощь. |

Источник: руководства WFH по лечению гемофилии, 3-е издание (2020 г.). Более подробную информацию о гемофилии можно получить из руководства на веб-сайте https://elearning.wfh.org/ru/resource/guidelines-for-the-management-of-hemophilia-ru/

© 2025 World Federation of Hemophilia